(8 min read) This three-part essay is a detailed case study of the greatest Gothic portals of all time. Part I provides an overview of the Gothic portal, a brief look at all nine portals at Chartres Cathedral, and a detailed examination of the three west portals. Parts II and III are about the north and south transepts, respectively.

Chartres Cathedral (officially “Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres”) is often cited as the greatest Gothic cathedral of all time. I don’t think this is true: the top dozen or so are all more or less tied, and picking out one over another as the absolute best becomes subjective and academic.

That said, when you decide to focus on specific aspects or elements of cathedrals, then picking out a single most “this” cathedral or a cathedral with the absolute best “that” is often possible. And I am convinced that Chartres Cathedral’s portals, considered as a whole, are — due to their size, number, and conceptual complexity — most definitely the greatest set of Gothic portals ever created.

They are also an excellent case study for understanding all Gothic portals. There are very few features, iconographies, or narrative themes found elsewhere that don’t also occur here. If you have a good understanding of Chartres’ portals, you will have the keys to understanding pretty any Gothic portals you come across (as well as a lot of Romanesque, Renaissance, and Baroque ones).

So in this and the next two posts we will take a close look at all of Chartres’ portals. In this post I’ll provide an overview and a look at the west portals. In Part II, we will check out the north portals; finally, the south portals will be the subject of Part III.

The Gothic Portal

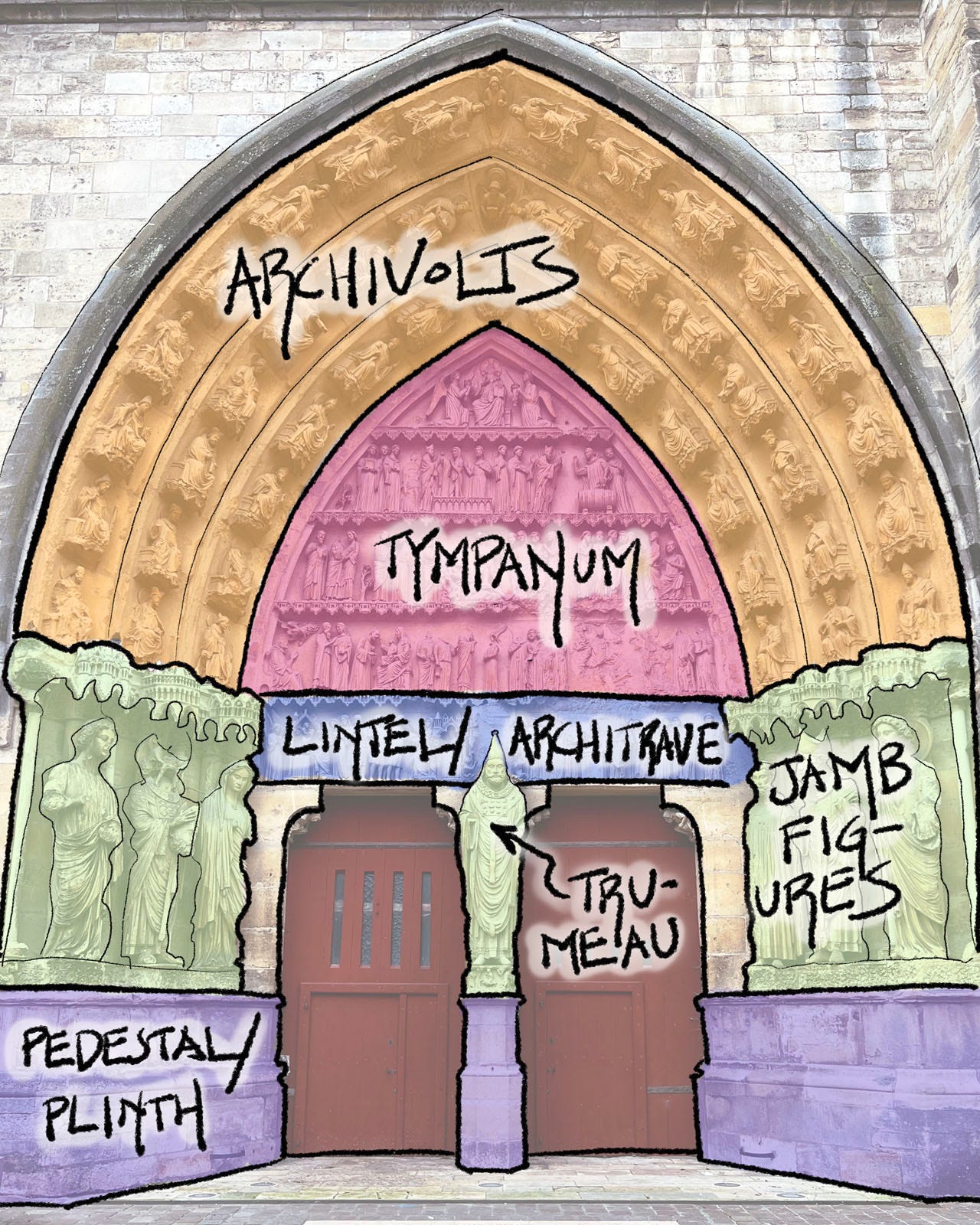

First, however, I’d like to discuss the Gothic portal in general. Figure 1 is a north portal from Reims Cathedral, color-coded to show the main parts and the architectural terms for them, which I will be using frequently over these posts. (By the way, this figure is also the final figure in my post “The Parts of a Gothic Cathedral,” which is worth reading before this one if you haven’t already.)

A good Gothic portal takes the entrance into the church and turns it into an educational celebration of art and architecture. While Gothic churches are often filled with architecturally-integrated art, the entrance is where the devout get closest to the building. And so the clergy who designed the conceptual programs, and the artisans who made the religious ideas come to life, took this fact to heart and surrounded the main entrances into the church with figures and narratives from the Bible, saints lives, and even secular symbols and motifs.

You’ll see a lot of this played out in Chartres’ portals, and by the time we’ve reviewed all nine (there are three sets of three) you’ll see that the portals here integrate virtually every major element of the medieval universe into the cathedral’s entrances. Moreover, they did so in a manner that links all three sets to each other through a chronological telling of the Church’s history, as it was understood at the time.

The story begins with the north transept’s theme of the Old Testament and “precursors to the Christ” (figure 2).

Walking counterclockwise around the cathedral from the north transept to the west facade, we see the theme of “Christ in the world,” with the story of Jesus’ life on earth.

Continuing on to the south transept, we see the “post-Christ’s life” of the Church, with saints forming one of the main subject matters.

Though the chronological narrative develops in this way from north to south, we are going to begin our survey with the west portals because they were the ones first created, from around 1145-55. The north transept portals were done some 60ish years after that, and they will be the subject of Part II of this essay. And the south transept portals, completed 10-20 years after the north (so around the 1220-30s), will be the subject of Part III

The West Portals of Chartres

The west portals, also called the “royal portals,” are the oldest of Chartres’ three sets of portals. In fact, interestingly enough, they actually predate the rest of the cathedral we see today. The previous cathedral burned down in 1194, which prompted rebuilding in the then-new Gothic style. However, one of the few things to survive the destruction was this set of three portals (figure 5), so they were saved and moved into their present positionwhen the new building was constructed.

These portals date from 1145-1155 and are in a transitional style from late Romanesque to early Gothic (recall from my post “Two Short Histories” that Gothic was “born” not far from here in 1144). I really love in particular the elongated bodies, beatific countenances, and shimmering robes of the Old Testament jamb figures here (figure 6). Though later portals will become more elaborate (both here and in other cathedrals), this was groundbreaking work and highly influential.

Note that while each set of doors has its own individual tympanum, lintel, and archivolts, the jamb figures run continuously between all the doors, forming them into a whole. Moreover, the capitals above their heads form a continuous frieze depicting the life of Jesus (figure 7).

The West Right Portal

The west right portal (figure 8) begins our narrative with the theme of the birth of Christ.

Unidentified kings and queens of the Old Testament form the jamb figures, while the tympanum and lintel above (figure 9) show well-known scenes such as the Annunciation and Visitation and Nativity with Shepherds in the bottom register, a Presentation at the Temple in the middle, and a Virgin & Child (in the “Throne of Wisdom” iconography) at the top.

In figures 8 & 9 you can also see the archivolts, with a detail shown in figure 10. These show the seven liberal arts (probably a nod to the School of Chartres, an important institution in the 11th century) and their most famous ancient practitioners. For example figure 8 shows personifications of Music and Grammar above, with Pythagoras and Donatus below.

The West Central Portal

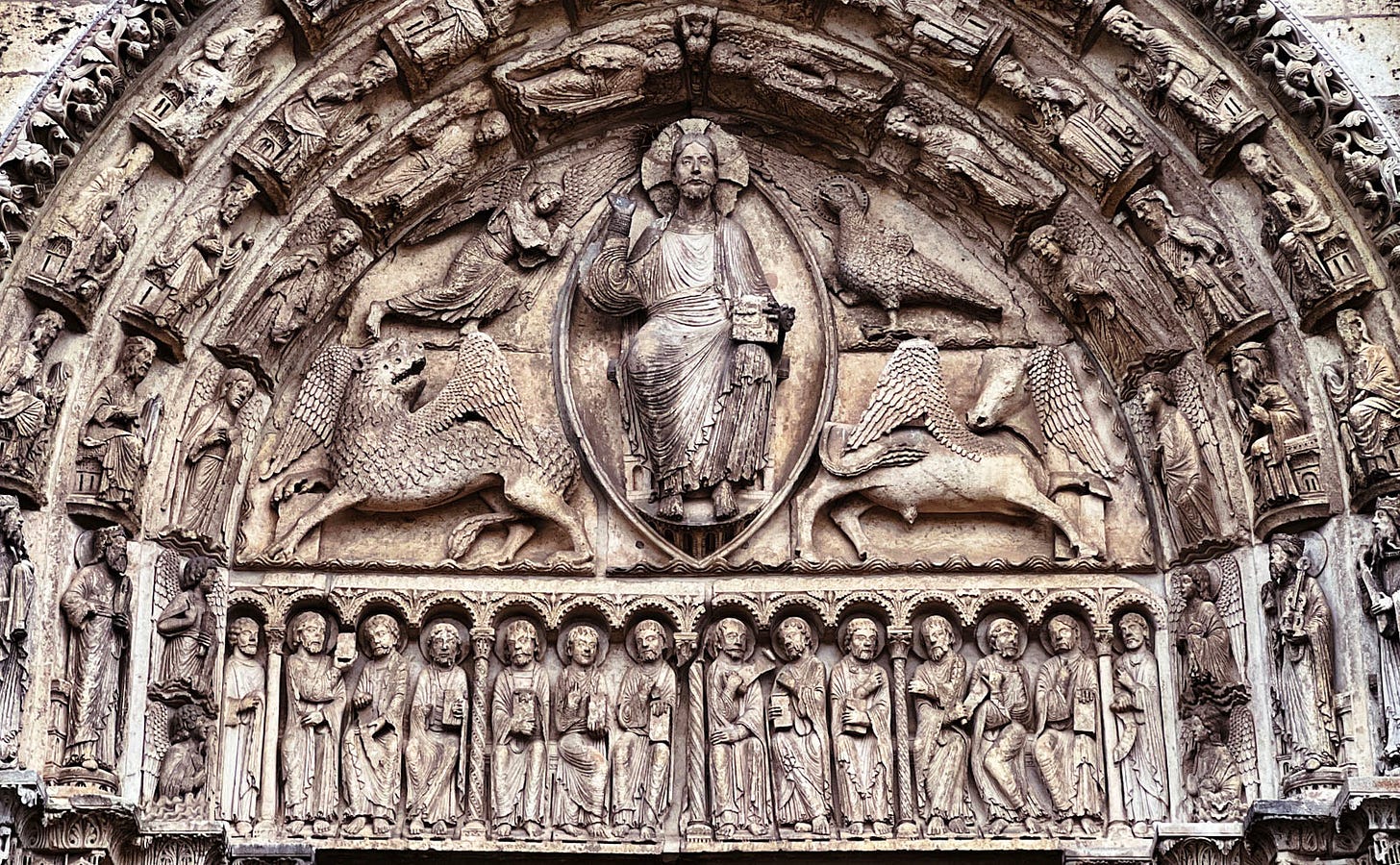

The central portal of the west facade here is larger than the other two (figure 5), which is typically the case when Gothic portals are combined into sets of three (or occasionally five). The tympanum here (figures 11 & 12) does show any narrative per se but instead has standard “Christ in Majesty Surrounded by the Four Evangelists” iconography. In the lintel below (also figures 11 & 12) are the twelve apostles as well as Elijah & Enoch (WHY?).

In figure 12 you can also see the jamb figures; these are more Old Testament personages, a couple of whom have been identified as Moses and Solomon (I do not see it but Emile Male did, and I am not one to argue with him on questions of medieval iconography).

The archivolts here, visible in figures 11 & 12 and detailed in figure 13, show angels and Elders of the Apocalypse, suggesting that this portal was intended to show the Christ in his final glory at the end of time.

The West Left Portal

The tympanum and lintel (figure 14) of the left portal is open to various interpretations, but I am with the majority when I say that the tympanum shows the ascension of Christ into heaven with ten apostles below watching.

The archivolts here, visible in figure 14 and detailed in figure 15, show the signs of the zodiac and personifications of the months.

I am not sure why some of the jamb figures here are standing on other figures below (figure 16), unlike the other portals here, but there has been a lot of damage and reconstruction to virtually all Gothic churches over the centuries, leading to curious anomalies like this.

This concludes our overview of Chartres’ portals and tour of the west facade’s set. In Part II of this series we look at the north transept’s portals.

I've just started your essays and really enjoying them. My son and I spent a day at Chartres about 12 years ago and were overwhelmed. And your pictures are awesome reminders!

The tympanum & archivolts on the west central portal appear to me to be representing Christ on the throne from Revelation 4 & 5. This would align with the theme "Christ in glory". Christ is standing on the throne (more or less standing). Surrounded by the 4 Living Creatures (angels) - #1 Like a lion (lower left), #2. Like an ox (lower right), #3 face like a man (upper left), #4 like a flying eagle (upper right). Then he is encircled by angels (as the first circle is with wings), and then by 24 elders (2 rows of 12 each). They did a wonderful job of portraying the "encircling" of the throne that is repeated in those two chapters. Thanks again! - Russ

>In the lintel below (also figures 11 & 12) are the twelve apostles as well as Elijah & Enoch (WHY?).

Elijah and Enoch do have something theologically important in common: they are the only two humans who never died. Enoch “walked with God: and he was not; for God took him” and Elijah was carried up to Heaven in a chariot of fire. I’m not sure why they are paired with the disciples, but it may be that they are there because they were considered the holiest and most righteous Old Testament figures, or perhaps because they are certainly with God in Heaven.