Two Short Histories of Gothic Architecture

An Initial Introduction to the Gothic World

(9 min read) This is the first post in the Gothic section of my substack. It’s an early draft of the beginning of my work-in-progress book on the subject, and presented here as an orientation to Gothic architecture for newbies.

Lady Gothic

Lady Gothic was born and baptized just outside Paris on 11 June 1144, when the Basilica of St-Denis’ progressive new choir (figures 1 & 2), brainchild of Abbot Suger, was consecrated in the presence of King Louis VII and Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Her childhood and adolescence largely took place in France and England, and her passage to adulthood arguably occured in 1258 in Salisbury, some 250 miles from her birthplace, when the cathedral there (figure 3) — perhaps the most unified expression of Gothic ever created — was completed in a single 38-year building campaign.

As an adult, she spread across all of Western and Central Europe, expressing herself in ever new and more elegant forms as she entered new regions and became older and more self-possessed (figure 4, for example).

Slowly but surely, however, technological and social changes of the 15th and 16th centuries — things like the printing press, the discovery of the New World, and the Reformation — pushed her into old age.

Victor Hugo was on to something important when he said that “the book killed the building” — that is, the printing press ended the Gothic age. But if the printing press slowly drained her blood, the final death blows came in the Low Countries over two weeks in August 1566, when mobs of overzealous Calvinists ransacked hundreds of churches throughout the region and destroyed the religious art they contained, putting an end to Lady Gothic. The time of death was called on 20 August 1566, in Antwerp (figure 5).

A Less Short History

The above is a succinct and straightforward narrative, and it has the advantage of personifying the art movement we now call Gothic as a woman, which was a very medieval way of thinking about abstract concepts.

And while the preceding narrative is all correct, any such exact dates or blanket statements for a cultural phenomenon like Gothic are of course an oversimplification. Moreover, us moderns are more likely to think of artistic and cultural movements in evolutionary terms, a framework that was unavailable in the Middle Ages.

So let’s repeat the history — it will still be simplified and short, because this is just a blog post — with more subtlety and nuance, though the lens of cultural evolution.

On 11 June 1144, the choir in the Basilica of St-Denis was dedicated, and this architectural masterpiece is generally regarded as the first work of Gothic architecture (figures 1 & 2 above) .

This was the first time that the main elements of what we now call Gothic architecture — pointed arches, ribbed groin vaults, and large windows of stained glass — were brought together for the first time. The actual masons and other builders who made this happen are unknown to us, as is typical for medieval craftsmen and artisans, but Abbot Suger — Abbot of St-Denis from the 1120s until his death in 1151 — was a key player in its creation.

The Gothic mode didn’t suddenly appear, however. It evolved from Romanesque architecture into a distinct art form, the result of many incremental stylistic and technical changes made by many minds and hands over the course of a couple centuries

Hints of the Gothic, for example, can be seen in the abbey churches built by Wiliam the Conqueror and Queen Matilda in Caen, France starting in 1066. Both feature ribbed vaults, but those at Matilda’s Trinity Abbey (figure 6) are still rounded and only in William’s side aisles (figure 7) do we see an attempt at a slight point. And neither building did much at this time to open the walls with larger expanses of glass.

Meanwhile, Lisbon’s cathedral, which was started in 1147 — three years after the choir at St-Denis was completed — features a very conservative barrel vault in its nave (figure 8), with chunky ribs that might seem more at home in a church from a century or two before. Stylistic movements always overlap, and as they move into different regions and cultures, they take on variations, much like subspecies in the world of living things. When Gothic did make its way to Portugal (as I will discuss below), it would result in a very different style than you see in France and England. There are dozens of regional variations into which you could classify Gothic architecture, were you so inclined.

Stylistic shifts in art and architecture also reflect deeper social changes. Economic, technological, political, and ideological changes in the 11th and 12th centuries played critical roles in the transition from from Romanesque to Gothic. For example, it is no coincidence that Gothic took its earliest roots in England as well as northern France. Those transitional examples from Normandy that I mentioned above would very much inform the English after William’s conquest. Likewise Eleanor of Aquitaine, there at the dedication of St-Denis in 1144 as Louis VII’s queen, would soon enough become English King Henry II’s queen, pointing up the strong ties between the French and English at the time.

And so Gothic — imagining it as a species that took over large swaths of European art for a few centuries — didn’t “die” on a specifically identifiable date, but instead was outcompeted in the new political, technological and cultural environments created during the 15th and 16th centuries various Renaissance and Reformation movements.

Moreover, the Reformation movements went far deeper than stylistic changes, and were as much a “revolution” as a “reformation.” Rejection of the ideas behind — and the art inside of — Gothic churches was a key component of of almost all the Reformation movements.

Violent iconoclastic outbreaks occurred sporadically in northern Europe from the 1520s through the 1650s when ideologues would spur mobs to ransack churches and destroy the ostensibly idolatrous art they contained.

I pinpointed the month of August 1566 and the place of the Low Countries (modern day Belgium and the Netherlands) — when mobs of overzealous Calvinists descended on hundreds of churches in over a dozen towns to destroy their art — as an especially important moment. It might not have been the first wave of iconoclasm, but it sent shockwaves throughout Europe and was the first that truly represented the momentous societal shifts that were taking place, from the old medieval order to the early modern world.

These were the first stirrings of what would become the Dutch Rebellion, a war between Philip II of Spain, protector of the “true religion” and old medieval order — Christendom, as it was still known at the time — and the people who would eventually become the Netherlands and help give birth to the liberal political organizations and worldviews that probably anyone reading this book takes for granted today — the modern West, in today’s parlance.

Despite the world moving into the modern era, however, thousands of individual Gothic buildings lived on through various alterations and additions. That is how we encounter them today, in fact: often with Baroque altarpieces, new windows, and other elements quite unlike their appearance in the Middle Ages.

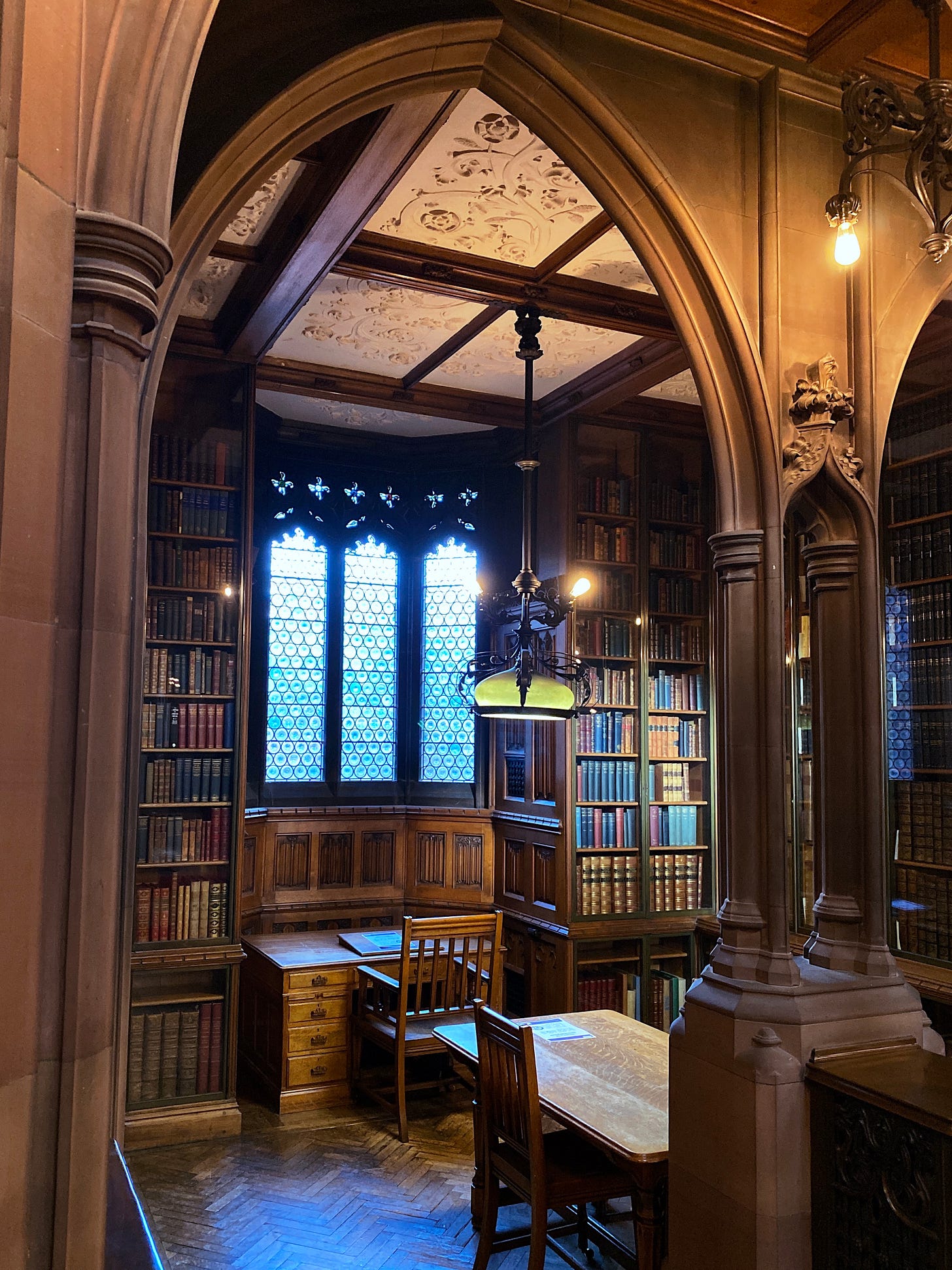

Moreover, the Gothic ideal was never fully wiped out, despite the disdain heaped on it by the taste-makers of the Renaissance and Enlightenment. In one of those many generational swings of taste, Gothic was resurrected to great effect in the 19th century — the 1890s John Rylands Library (figure 9) in Manchester, England is a beautiful example — and still lives on in various fashions.

The inaugural year of 1144 is widely accepted among scholars in the field as the start of the Gothic period, but my use of 1566 is probably a good deal later than you expected: after all, didn’t the Renaissance began in Italy a couple centuries before that?

Just as cultural movements like this don’t suddenly appear, they also fade away more slowly than it often seems in retrospect. In addition, these movements overlap both chronologically and geographically. So while the “Renaissance” did indeed begin in the 14th and 15th centuries, it was only in Italy that it really took on the Neoclassical flavor we often associate today with the period. In many parts of Europe, and especially in the northern parts, Renaissance ideas were explored and executed very much within the Gothic idiom.

A lot of great late Gothic work was still going on the 16th century, and it shows an incredible amount of variation and elaboration from the earlier examples I showed above.

For example, the Portuguese were building the late Gothic style known as Manueline — with influences from the Italian Renaissance and Arabic Africa mixed in with nautical themes all through the 16th century, as Belem Tower (figure 10), finished in 1519, and Jeronimos Monastery (figure 11), primarily built from 1501-1601, still attest. And in England, the Perpendicular masterpiece King’s College Chapel in Cambridge (figure 12) was not completed until 1515; work in the same style continued on Bath Abbey (figure 13) through 1611, despite England’s dissolution of the monasteries and the subsequent destruction of religious art and architecture from 1536-1541.

This should all suggest to you that there is no true single moment or location for the beginning or ending of the Gothic movement. Most of the art and architecture we will discuss here will be work that was done in Western Europe from about 1150 to 1550, though we will also inevitably explore periods and regions outside this as well. Likewise, the photographs will show the buildings as they exist today: often with major Romanesque components that preceded the Gothic, and/or with art, furnishings, and additions from Renaissance, Baroque and even modern periods.

While the most (and arguably the greatest) examples of Gothic are to be found in France and England, Spain, Belgium and Germany have their fair share of amazing examples as well. And the style spread throughout almost of all of Western and Central Europe. We will look at examples from Portugal to Poland, and from Scotland to Italy. In fact, you can even find contemporaneous examples of Gothic architecture, at least in ruined form, as far away as the Levant: figure 14 shows some 13th century Gothic vaulting built in Caesera, Israel when it was part of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, one of the many Crusader states that lasted from 1098 to 1291.

In short: the time and place we are entering in this section of Both/And is the European High and Late Middle Ages, and Gothic in a sense represents the ultimate artistic flowering of the medieval mind before it came to be replaced by the beginnings of the modern world.

Was this history too short for you? Of course it was! Stay tuned to learn more about the history, art and culture of the Gothic world.

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **