Introducing the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic

A Year-Long Countdown of Gothic Masterpieces

(10 min read) This is the first post in a year-long exploration of the all-time greatest works of Gothic architecture, introducing the ideas and criteria that will guide the rest of the series.

Every Saturday over the course of 2025, I will be counting down the fifty greatest works of Gothic architecture with a photo essay about a specific building (or building complex).

[Edit, 26 August: Starting with number 17, the series will shift to bi-weekly. It will finish on 11 April 2026.]

Each essay will include a potted history of the building and a photographic “virtual tour” through it. I will also discuss what makes it special and why it warrants inclusion in the list; this discussion will sometimes include a little meta-analysis of whether and how lists like this can even be useful.

To see the entire list (so far), go to the page “The Greatest Gothic Architecture,” which will be updated each time I publish a new photo essay. The full list will be finally revealed at the end of the year, when I publish the essay on the building that I have decided is the absolute best.

In this introduction, though, I want to explain my criteria for judging these buildings as well as begin the meta-analysis of such surveys, by critiquing my approach.

Objective Subjectivity

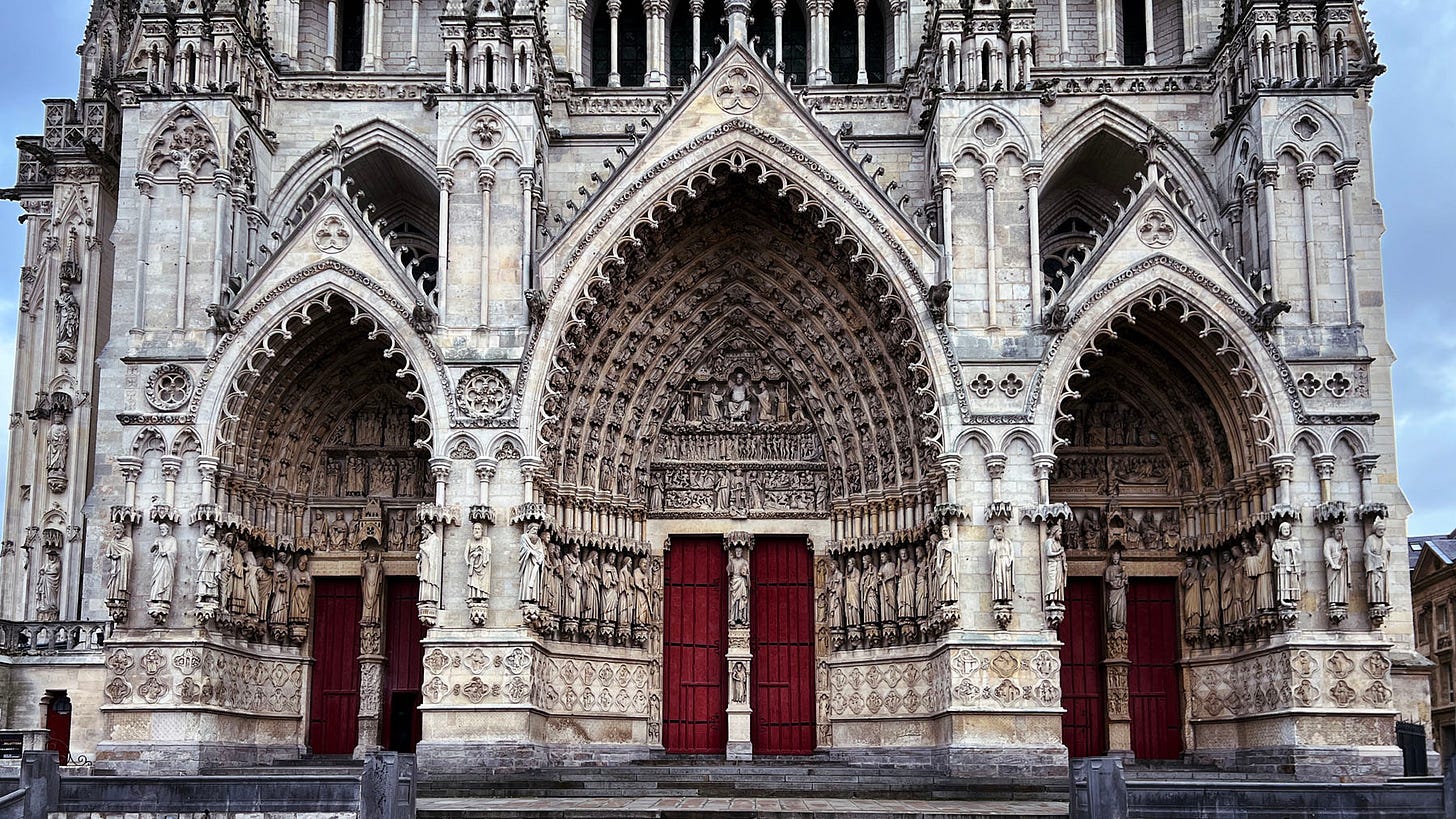

While lists of the greatest works of art, architecture, music, etc are of course subjective, that subjectivity isn’t total. There are indeed objective reasons for saying that Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue” is greater than any album by Kenny G, or that Amiens Cathedral is greater than any parish church.

Simultaneously, the objective reasons by which you determine the greatness of a work of art are not total, either. So whether Amiens Cathedral or Canterbury Cathedral is “better” (or whether “Kind of Blue” is better than “Bitches Brew”) is to some extent quite subjective, and an expert on the subject (or even a well-informed enthusiast) could make legitimate arguments on either side for placing one building or album above the other.

What we have then, when it comes to rating and ranking works of art, is a kind of objective subjectivity (or vice versa). Deciding between objects of distinctly different degrees of excellence is fairly straightforward, but things become much fuzzier when the objects are very close in overall quality but have very different specific traits.

That’s why any such survey as mine needs to be taken with a grain of salt. On the one hand, I am indeed expert enough in Gothic architecture that it would be hard for anyone to argue that any of my choices are completely off-base, especially if they read my photo essay explaining my reasoning. On the other hand, I would be open to good arguments as to why my #4 should actually be #2 or #7, or why my #49 shouldn’t be included at all and instead another building that is not in my list should take its place.

I strongly suspect that the highest levels of my countdown (say, the “top ten”) would correlate very closely with any architectural historian’s — exact rankings might change, and there might be 1-3 buildings that are completely different between them (most likely in the spots of 8-10), but our lists would be very close.

On the other hand, the buildings I rank as 40-50 might well be completely different from anyone else’s. As we get into less and less obviously majestic works of architecture, personal interests and idiosyncrasies play a more and more important role.

And on top of the personal idiosyncrasies that play a role in creating such surveys, there are also more straightforward reasons that my judgements might differ from those of another with similar expertise — the criteria by which we each assess a building. For example, how important is the role the building played in political or cultural history? How important is the current state of the building? Does artistic uniqueness play any role, and if so how much of one?

Knowing a person’s criteria for judgement is important if someone wants to fully understand and critique a list such as the one I am creating here. Perhaps, then, it is time to look at mine.

** Please hit the ❤️ “like” button❤️ if you enjoyed this post; it helps others find it! **

My Criteria

Here are the main factors I considered when determining whether a piece of architecture warranted a spot in a “top fifty” survey, and deciding exactly what ranking it should have.

Personal Documentation:

To date, I’ve photographically documented over 360 pieces of Gothic and “Gothic-adjacent” (Romanesque, Gothic Revival, Gothic-Renaissance hybrids, etc) architecture — see my post “A Note on Process & Method” for more about that.

So the first criterion for inclusion in my list is that it is one of these 360+ buildings. While that may at first glance seem very limiting, I don’t think it is, especially when it comes to the top 25-30 buildings.

My choices of places to visit weren’t random, of course: I specifically visited the most renowned works of architecture that I could, and I also purposefully visited a wide range of regions, from Portugal to Poland and from Scotland to Italy. I am fairly certain that there are no buildings any expert would put in a top ten list that I have not personally documented, and only a very few buildings that could legitimately be put in a top twenty list that I have not documented.

It is only when we get into the rankings of 30-50 that I think my requirement of having personally documented the architecture is at all limiting, and even then, the limitations are marginal. My initial shortlist of candidates for this exercise was over sixty, and I found it hard to cut some of the buildings from my list — there’s a lot of amazing Gothic architecture out there.

Gothicness:

This criterion includes a couple aspects. Firstly, I only considered architecture from the original age of Gothic, which ended over the course of the 16th century. No Gothic Revival or Neogothic buildings were included, even though I can think of a few that could have made the cut. (That said, many of the top fifty buildings have had some Gothic Revival renovations and remodelings, and I will often include these in the photographic showcase of the building.)

But “Gothicness” also reflects the fact that most great Gothic buildings were built over several centuries and therefore frequently incorporate multiple styles. In particular, Romanesque (from which Gothic evolved, as I describe in “The Evolution of Gothic Architecture, Part I”) buildings were often the foundation for later Gothic additions or reconstructions. Durham Cathedral, for example, is heavily Romanesque/Norman, and — while I do include it in my list — I did not rank it as highly as I would have if my series was the “Fifty Greatest Medieval Cathedrals.”

Similarly, the cathedrals in Trier and Speyer are amazing buildings worthy of inclusion in any list of “Fifty Greatest Medieval Cathedrals.” But both have only the slightest of Gothic elements, and so neither appears in my countdown.

Historical Importance:

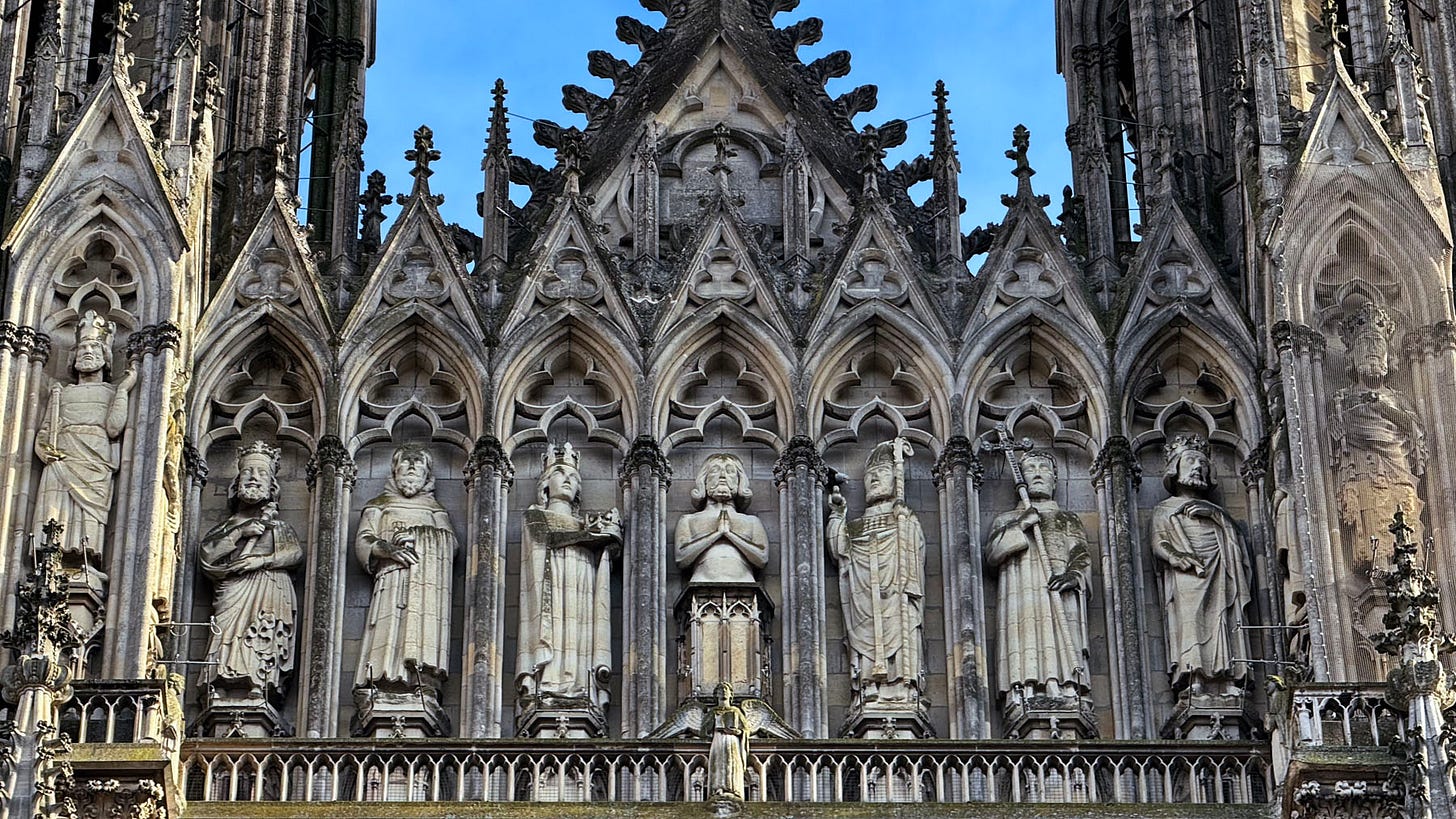

I gave more weight to a building’s historical, political, or cultural (as opposed to purely “architectural”) importance than some other people might. For example, Reims Cathedral was long the site of coronations for French kings, and Westminster Abbey is still the coronation site for British monarchs. Both would have appeared in my list even if this were not the case, but I also ranked both more highly than I would have if they did not play this important role in history.

Innovation:

Similarly, technical and/or stylistic innovation, especially when it became an influence on later architecture, is something that led me to rank a building more highly.

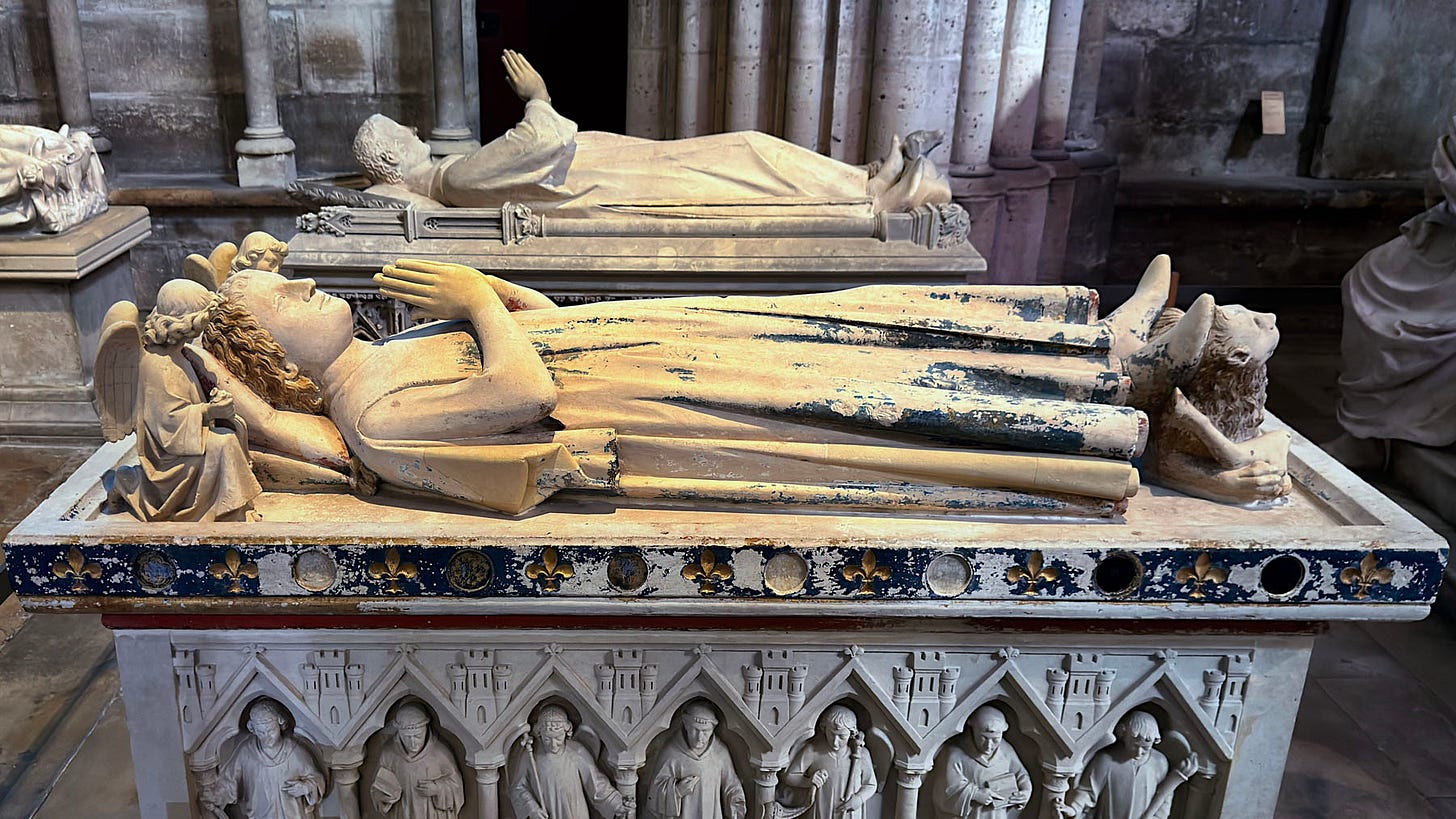

The Basilica of St-Denis — considered the birthplace of Gothic architecture, as I have described (repeatedly) — is a prime example of a building that would be considered great even if it had not been the first. But due to its role in spurring on the entire entire Gothic movement, my ranking of it is higher than it would be if it had no such role. (Interestingly, St-Denis also rates highly in “Historical Importance” since it was the burial place for French monarchs for many centuries, and contains the tombs of dozens of French royalty.)

Size:

All else equal, bigger is better. Smaller buildings do appear on my list, but generally speaking I rate cathedrals more highly than chapels of equal beauty, for example. Similarly, a great abbey church with an attached monastery complex will be rated more highly than the same church would have been if it stood alone.

Artistry:

All else equal, more beautiful is more better. This is the most subjective aspect of my criteria, but it of course must play a role in the curation of any list of greatest works of art or architecture.

Regional & Stylistic Context:

Some works represent unique local adaptations of the Gothic idea, and in the interest of providing a broad range of examples and showing the full extent of Gothic’s “manifestations” as it spread across Europe, I have included a few buildings in my survey (usually ranked around 40 to 50) that might not have otherwise made the cut.

For example, Belem Tower (Portugal) is a prime example of the late Gothic sub-style called Manueline; if no better examples had existed it would have made the list, espcially since its function as a defensive tower is highly unusual. However, better examples do exist — and you will learn about some of them in due time.

Similarly, I made sure to include at least one entry from each country in which I have documented a Gothic building (except for Luxembourg and Rhodes (Greece), because the Gothic buildings I saw in those places simply cannot be justified as a “top fifty” work).

Preservation Level:

My final major criterion is the preservation level of the building; this affects my rankings in two ways, both of which are about the visitor experience.

Firstly, buildings that are very well-preserved are ranked higher than those in a state of poor repair, and those that have retained a Gothic character are rated higher than those that have later additions or renovations that completely change the interior.

For example, if a Gothic cathedral’s interior is currently in a massive state of disrepair, or was massively redone in the 17th-18th centuries with Baroque renovations, I will downrank it accordingly — a heavily Baroque interior may prevent an otherwise strong contender for the top fifty from appearing. (As I mentioned above however, I do not consider a Gothic revival remodeling a negative, as they were done in the same spirit as the original movement.)

The second way in which preservation level — and preservation efforts — affect my rankings is that sometimes large sections of a building were off-limits when I visited, which hinders my ability to properly judge it (and will likely prevent you from fully visiting it any time soon as well).

Tournai Cathedral is a good example of this: from what I have read, it’s eastern half is an impressive enough example of Gothic that it should have perhaps been included in the 35-45 range of my rankings. But when I visited, the entire area was completely closed off for renovation and all I could really see was the Romanesque nave. It therefore does not appear in my list.

In Conclusion

This survey isn’t simply about showcasing the best examples of Gothic architecture. As I described above, and as you will see if you follow me through the series over the course of the year, it is also about how we (as individuals and as cultures) go about judging artistic achievements and determining what makes things great.

As I said near the start of this post, any list like this should be taken with a grain of salt. It should also be treated as a starting point for discussion rather than an end-all determination of an unassailable artistic canon. So if you have thoughts on the individual buildings I eventually present or the rankings I give them — or even the ideas and criteria I presented above — let me know in the comments.

This will make a great Saturday pleasure.

Thank you for this.