(12 min read) This extended photo essay is an exploration of how Gothic architecture evolved over the centuries. Parts I & II are being published on 31-Aug and 7-Sep 2024, and are a concise description of Gothic evolution from the early 12th to mid-16th centuries. Additional parts, exploring specific niches and regions, will be published intermittently into 2025.

In my post “The Mystical Roots of Gothic,” I described how a desire to recreate the mystical experience in architectural form was an important impetus for the Gothic style of architecture. Specifically, the metaphor of divine light as representative of mystical unity with God and the idea of creating a “Heavenly Jerusalem” inside the cathedral were key drivers in the Gothic impulse.

In addition, in my essay “Two Short Histories of Gothic Architecture,” I described the spread of Gothic architecture in evolutionary terms, as a cultural phenomenon born in northern France which then spread across Europe over a few centuries, changing as it did so. (And since cathedrals were often built and rebuilt over many centuries, sometimes these changes can be seen in a single building; the nave of Hereford Cathedral — figure 1 — is a good example, with a late Norman lower portion and early Gothic upper.)

Because of its spread and change over several centuries, scholars have developed dozens of substyles and phase” of Gothic architecture. For example, the English discuss their Gothic tradition in terms of Early, Decorated, and Perpendicular styles, while the French speak of Early, High, Rayonnant, and Flamboyant styles.

And when discussing the wider European phenomenon, things get even more complex: Brick Gothic, Sondergotik, Manueline, Mudejar, Brabantine, Venetian Gothic (figure 2), etc. The categorization can get very confusing, especially as the styles often start to blend into each other. Moreover, none of these were terms the original builders were using; they are all post facto creations of art historians.

These taxonomies can be useful, but I also think that it helps to mentally organize them if you can use some simple principles to account for the differences rather than try to memorize a long list of styles and their attributes. It is also a good practice to hold these categories loosely and not get hung up on whether a certain building is exactly style X or Y — there’s a chance it’s a little of both.

In terms of the principles for how Gothic evolved, two primary factors drove a lot of changes.

First, as the builders and artisans became more experienced in implementing the idea of creating “Heaven on Earth,” the buildings became more ethereal. Windows got bigger, spaces got taller, and ornamentation helped visually dissolve solid building components.

Secondly, as Gothic ideas and motifs moved out of the lands of its origin, they took on characteristics of the new regions it was entering. The pre-Gothic traditions of Italy, Germany, and Iberia, for example, were all quite different from northern France, as well as from each other. This led to different ways of interpreting the original French Gothic impulse.

While countercurrents and counterexamples can certainly be found, keep these two principles in mind — increasing “ethereality” over time, and different regional traditions for the “starting points” for Gothic ideas to attach to — and a lot of the differences you see from one Gothic building to the next will make conceptual sense, regardless if you know the exact terminology art historians use to differentiate one from another.

Romanesque & Norman Architecture

Gothic architecture was born in St-Denis, outside Paris, and its incubation and early spread was in northern France and England. (Recall that the 12th and 13th centuries were shortly after the Norman Conquest of England, and the houses that ruled both France and England were deeply intertwined, as were the populations. The “English” Plantagenet kings for example, often spent far more time in their French territories than they did in England.)

And since Gothic evolved in a pre-existing architectural context and tradition, in order to understand it we first need to understand the Romanesque architecture from which it evolved.

Romanesque — like Gothic — was a broad term, and had different expressions in different regions. In England it is often called “Norman” (figure 3, for example) and it is the later versions of Norman and French Romanesque that are most relevant to Gothic’s beginnings.

“…Tom thought about the cathedral he would build one day. He began, as always, by picturing an archway. It was very simple: two uprights supporting a semicircle. Then he imagined a second, just the same as the first. He pushed the two together, in his mind, to form one deep archway. Then he added another, and another, then a lot more, until he had a whole row of them, all stuck together, forming a tunnel… A church was just a tunnel, with refinements.

A tunnel was dark, so the first refinements were windows. If the wall was strong enough, it could have holes in it. The holes would be round at the top, with straight sides and a flat sill—the same shape as the original archway. Using similar shapes for arches and windows and doors was one of the things that made a building beautiful. Regularity was another, and Tom visualized twelve identical windows, evenly spaced, along each wall of the tunnel.” — Ken Follett, The Pillars of the Earth*

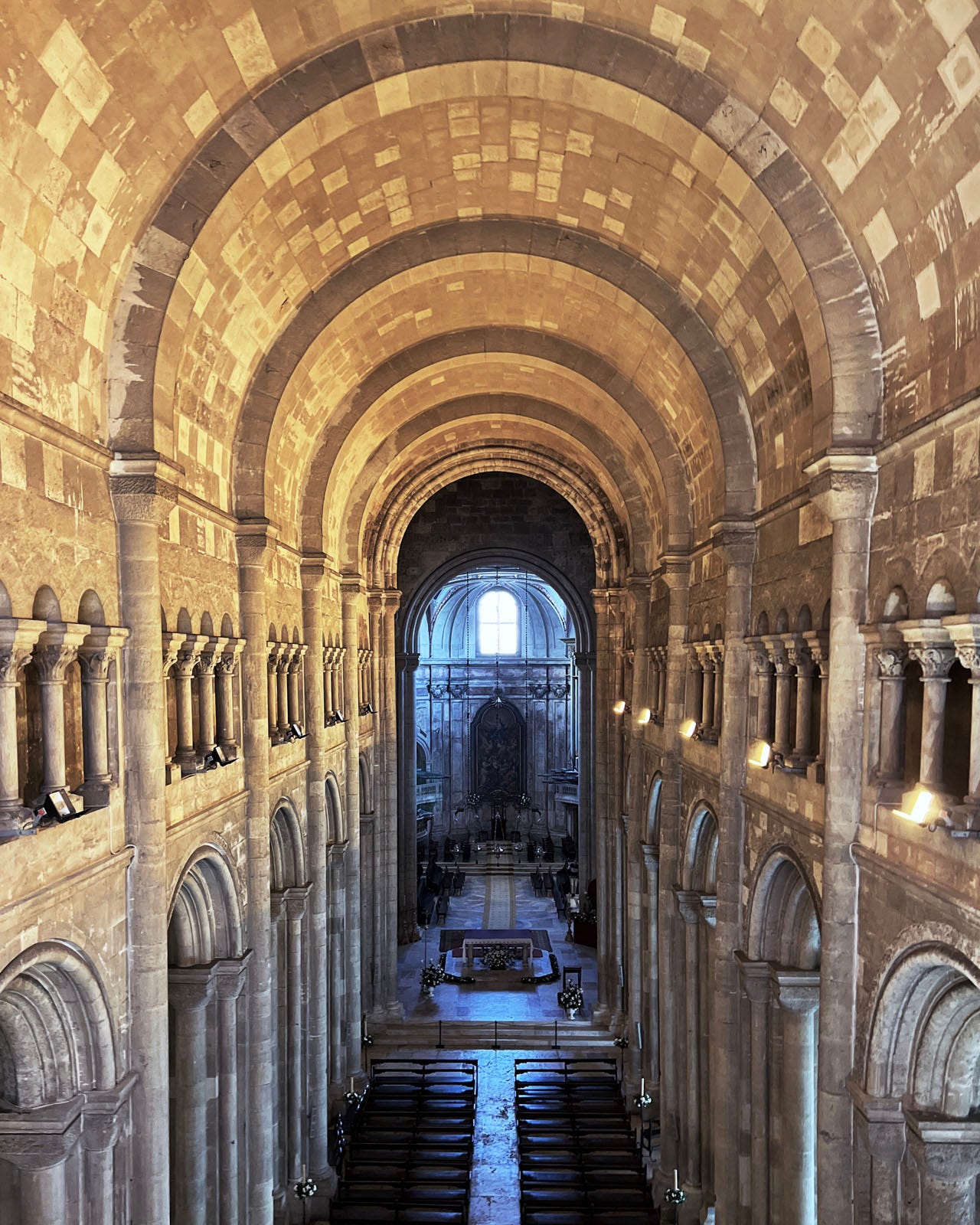

Follet’s Tom Builder is imagining the prototypical Romanesque church, and the phrase “just a tunnel, with refinements” is a succinct and evocative description of Romanesque architecture. And Lisbon’s cathedral (figure 4) is a good example of Tom’s tunnel.

Romanesque architecture is inherently heavier and darker than Gothic, but Lisbon’s cathedral is an extreme example. In fact, given that it was built from 1147 to c1200 — well after Suger’s groundbreaking choir at St-Denis (figure 13) — it is an example of a very conservative builder.

Romanesque architecture evolved from a combination of the Roman basilica and Byzantine church traditions, and while this process is beyond the scope of this post, suffice it to say that by the 11th and 12th centuries, it was well established across much of Europe as the ideal form of architecture for any significant church.

The essence of Romanesque architecture is the circular masonry arch. And though this form was often extended into what is called a barrel vault (Tom’s tunnel), a space could also be vaulted with domes, as the early 12th century church for Fontevraud Abbey (figures 5 & 6) show.

Similarly, a space could also be covered with groin vaults, as in the side aisles (figure 7) and chancel (figure 8) at the Abbey of Sainte-Trinite (aka the Abbaye aux Dames) in Caen. Caen was then the capital of Normandy, and the Abbaye aux Dames was built for Queen Matilda (wife of William the Conqueror) around 1080. As you can see in figures 7 and 8, a groin vault is produced when two barrel vaults at right angles to each other intersect.

“The Gothic Style evolved from within Romanesque church architecture when diagonal ribs were added to the groin vault” — Paul Frankl**

As suggested by preeminent 20th century Gothic scholar Paul Frankl’s quote, one of the key moments in transforming Romanesque into Gothic was the introduction of ribs in the groin vault at the diagonal where the two barrel vaults intersect. An early example of this is in the Abbaye aux Dame’s nave (figure 9), which originally dates from about 1130, as well as in the nave of Durham Cathedral (figures 10 &11), which dates from c1115-30.

The rib vault allowed for easier and more flexible construction, as well as reducing the amount of material needed and thus the loads on the columns below.

The next move that led to Gothic from Romanesque was the switch to pointed arches and vaults instead of hemispherical. The side aisles at William the Conqueror’s Abbey of Saint Stephen (aka the Abbaye aux Hommes) — built in Caen about the same time as Matilda’s Abbaye aux Dames — show very slightly pointed arches as the basis for the ribbed groin vaults (figure 12).

There are several advantages to pointed arches and vaults, but one of the most important for the next moves in the creation of Gothic is that they reduce the outward thrusting loads on the columns and walls. This means both can be thinner. As a side effect, it also means windows can be larger.

The Birth of Gothic

As described in my short history post, these three elements — the ribbed vault, pointed arch, and large windows — first came together in Abbot Suger’s reconstruction of the choir and ambulatory at St-Denis (figures 13 & 14).

The dedication here on 11 June 1144 was attended by many of France’s most powerful secular and religious rulers, including King Louis VII, his queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, and bishops from all over France. And the architecture was so impressive that it quickly spread across France and England. (As a reminder of the ties between these two countries, recall that ten years after this dedication Eleanor of Aquitaine became became Queen of England, as wife of Henry II.)

Early Gothic

While the new style was employed in many dozens of buildings over the next few generations, we can get a sense of them all by looking at three particularly “clean” examples: the cathedrals of Laon, Wells, and Salisbury. France’s Laon and England’s Salisbury are nice examples because they were both built in relatively short order by medieval standards and thus are pure examples of the early styles. Similarly, the western half of Wells’ main church structures were completed in a short timeframe and remain (relatively) unaltered by later work today.

Laon’s cathedral (figures 15, 16, & 17) was the first to be built entirely in the new Gothic style. Groundbreaking was in 1150 — six years after the dedication at St-Denis — and the church was essentially complete by c1235.

As figures 15-17 show, Laon is very much in the new Gothic style, with pointed arches and ribbed vaulting throughout, and much larger windows than in the Romanesque churches. As a result, the interiors feel much brighter, soaring.

At the same time — and especially relative to the later stages of Gothic that we will see in Part II — there is still a hefty, stoic feel here. The arcade columns are chunky and topped with classical capitals, arches are pointed but not steeply so, and the ribs — especially in the side aisles — are pretty chunky members.

This is indeed Gothic, but you can also tell that this is very much a cousin of the Romanesque abbeys in nearby Caen from a century earlier.

Wells Cathedral was the first in England to be fully rebuilt in the new Gothic style, and — while much of the east end was later rebuilt — the nave and side aisles (figures 18-20) retain their original construction and character.

A few refinements take this further from classic Norman/Romanesque than Laon: the arches are more steeply pointed, for example, and the “clustering” effect of moldings at the columns and arches — especially at ground level — help break them up visually.

We see these same ideas taken a bit further — and the space opened up even more — at the cathedral of Salisbury (figure 21), which was almost entirely built from 1220 to 1258.

These three examples of Laon, Wells and Salisbury are prime examples of what is called Early Gothic by both the French and English. As we will see in Part II, however, both the names and the substances of later stylistic developments will diverge as we move in the so-called High and Late Gothic styles.

Part II will be published on Tuesday. If you want to make sure to never miss a new post, then subscribe for free:

References

* — page 22.

** — Gothic Architecture, page 41.

Follett, Ken. The Pillars of the Earth. 1989.

Frankl, Paul. Gothic Architecture. 1962; 2nd ed 2000.