(8 min read) King’s College Chapel in Cambridge — 46th in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — is one of the most spectacular achievements of late English Gothic architecture. Built over the course of multiple reigns and political upheavals, it represents the height of Perpendicular, with its vast fan vaulting and luminous stained glass.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: King’s College Chapel, Cambridge

Official Name: King’s College Chapel

Location: Cambridge, UK

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1446-1515

Why It’s Great

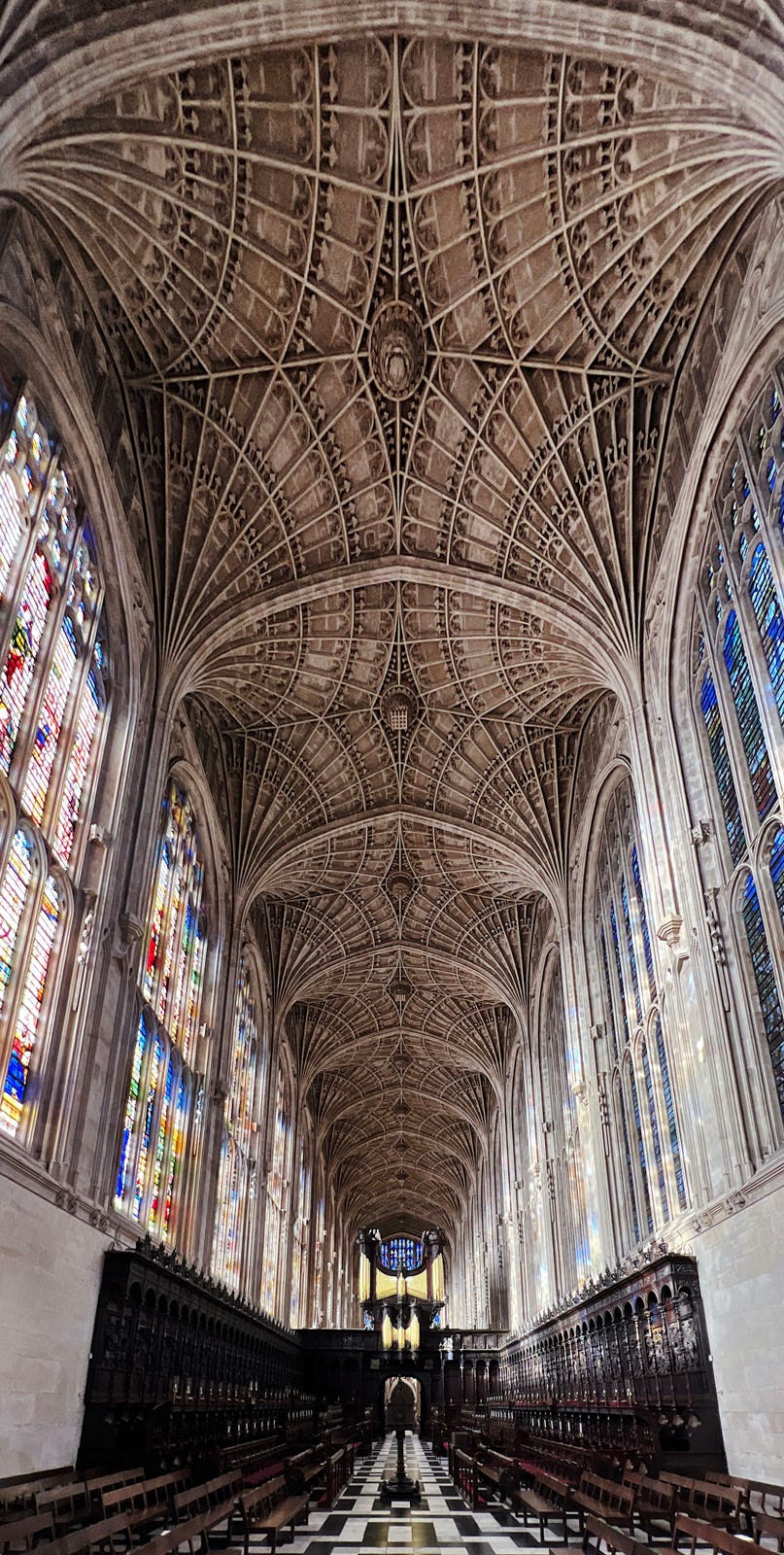

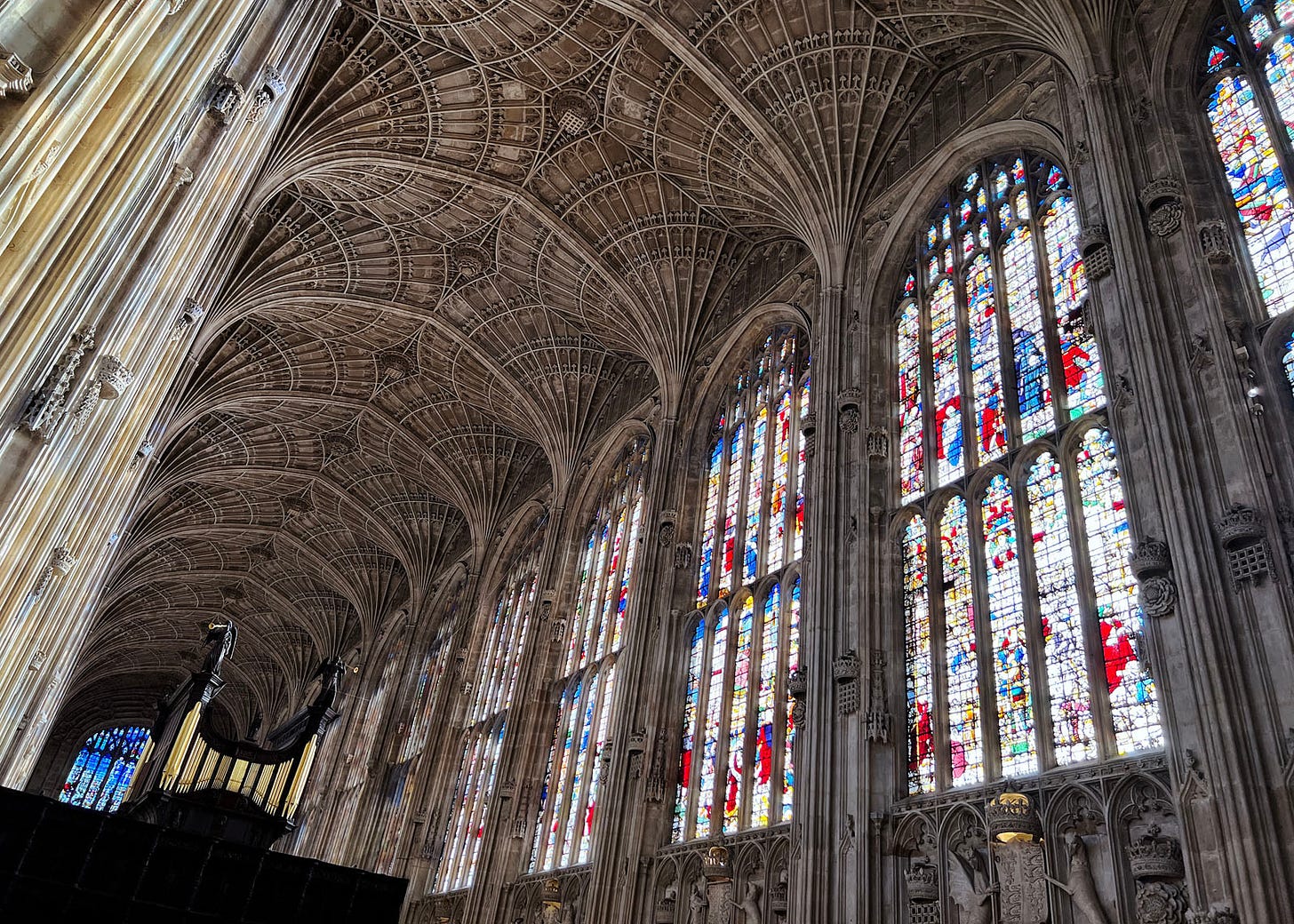

King’s College Chapel is the finest example of England’s final and most refined style of Gothic: Perpendicular. Its vast, uninterrupted interior, soaring windows, and world-record fan vaulting create an ethereal sense of space that was centuries ahead of its time.

Why It Matters: History and Context

King’s College Chapel is the finest example of England’s ultimate Gothic style, which is known as Perpendicular. (For more about the evolution of Gothic styles in England and France, check out my two-part essay here and here.)

When I wrote that Perpendicular was England’s “ultimate Gothic style,” I meant that in the temporal sense of being the final Gothic movement in England. After it, the Renaissance took over the architectural and artistic worlds (as we will see shortly, with the furnishings and windows here). But I also mean it aesthetically as well, at least on a personal level. I can see why some might prefer the clean lines of Early Gothic or the intricate detailing in the Decorated style, but I personaly love Perpendicular, especially when it includes lacy fan vaulting, as here (figure 3). In fact, the fan vaulting in King’s Callege Chapel is the largest in the world.

The entire building is an engineering marvel, frankly, and it shows how far Gothic builders had come in the two centuries since the disastrous Beauvais Cathedral (see #51 in this series).

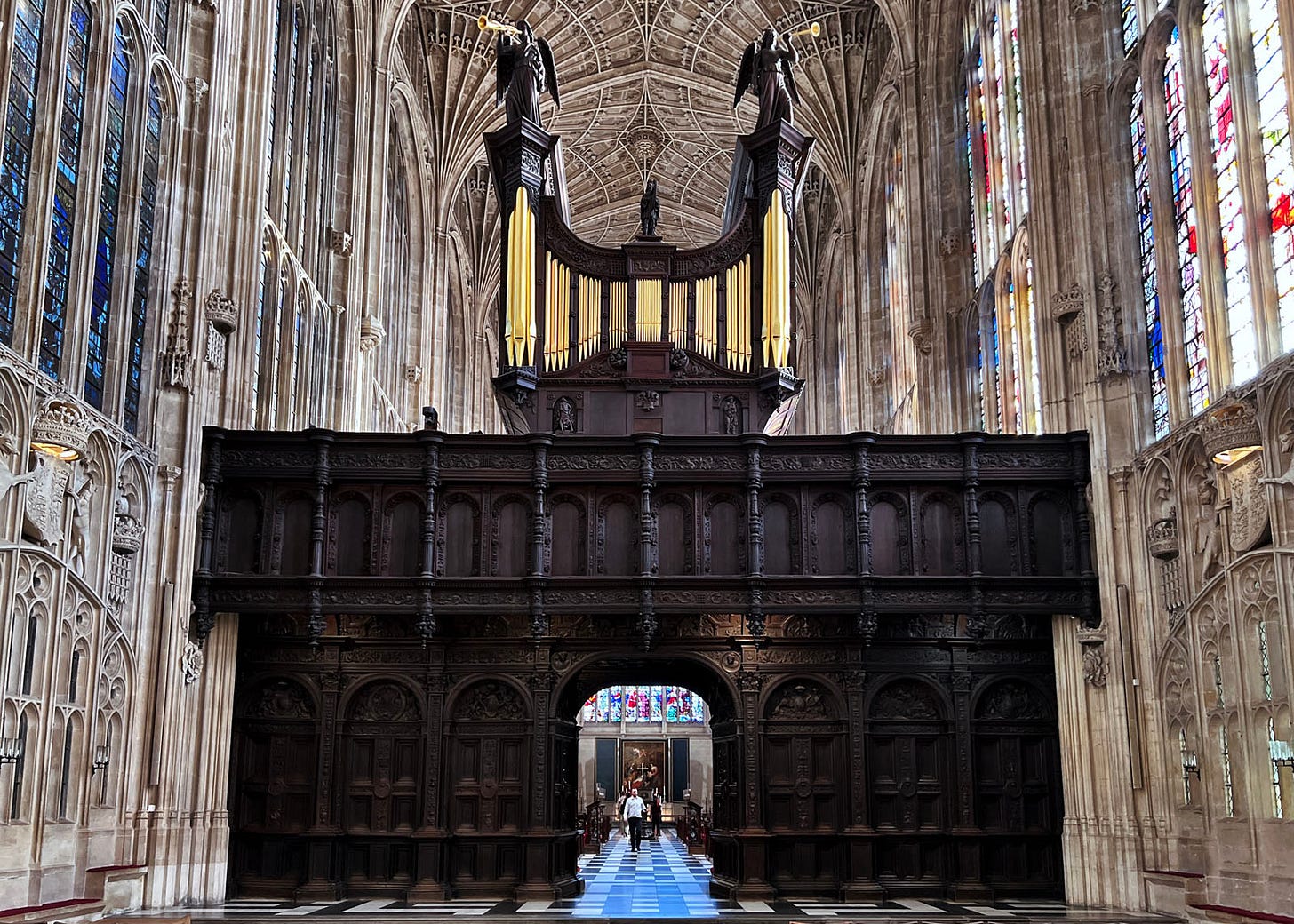

The interior is strikingly modern as well, with slender columns and massive windows creating a single open rectangular box. Completely open above and only interrupted at the ground level with a contrasting wooden rood screen, which holds up a massive organ, it really feels like a precursor to the minimalist spatial compositions of Mies van Der Rohe and Le Corbusier in the early 20th century. But this predates them by over 400 years.

The unified feel here is especially remarkable given that the history of construction is one of stops and starts under three different kings, dynastic change in the ruling house, and even a revolution in religious authority. The church was begun shortly before the Wars of the Roses broke out and not completely finished until after the English Reformation was underway.

King’s College in Cambridge was founded by Henry VI in 1441, and the foundation stone for the chapel was laid on 25 July 1446 by the king himself, part of a larger plan for a court that was never completed.

In 1455 the Wars of the Roses broke out, when Henry’s right to the throne was challenged by Richard, Duke of York. Construction slowed, and then completely stopped — with mostly only foundations in place — once the king was taken prisoner in 1461. Work did not resume until 1477 under Edward II; this phase lasted through the reign of Richard III, which ended in 1485 along with the Plantagenet dynasty.

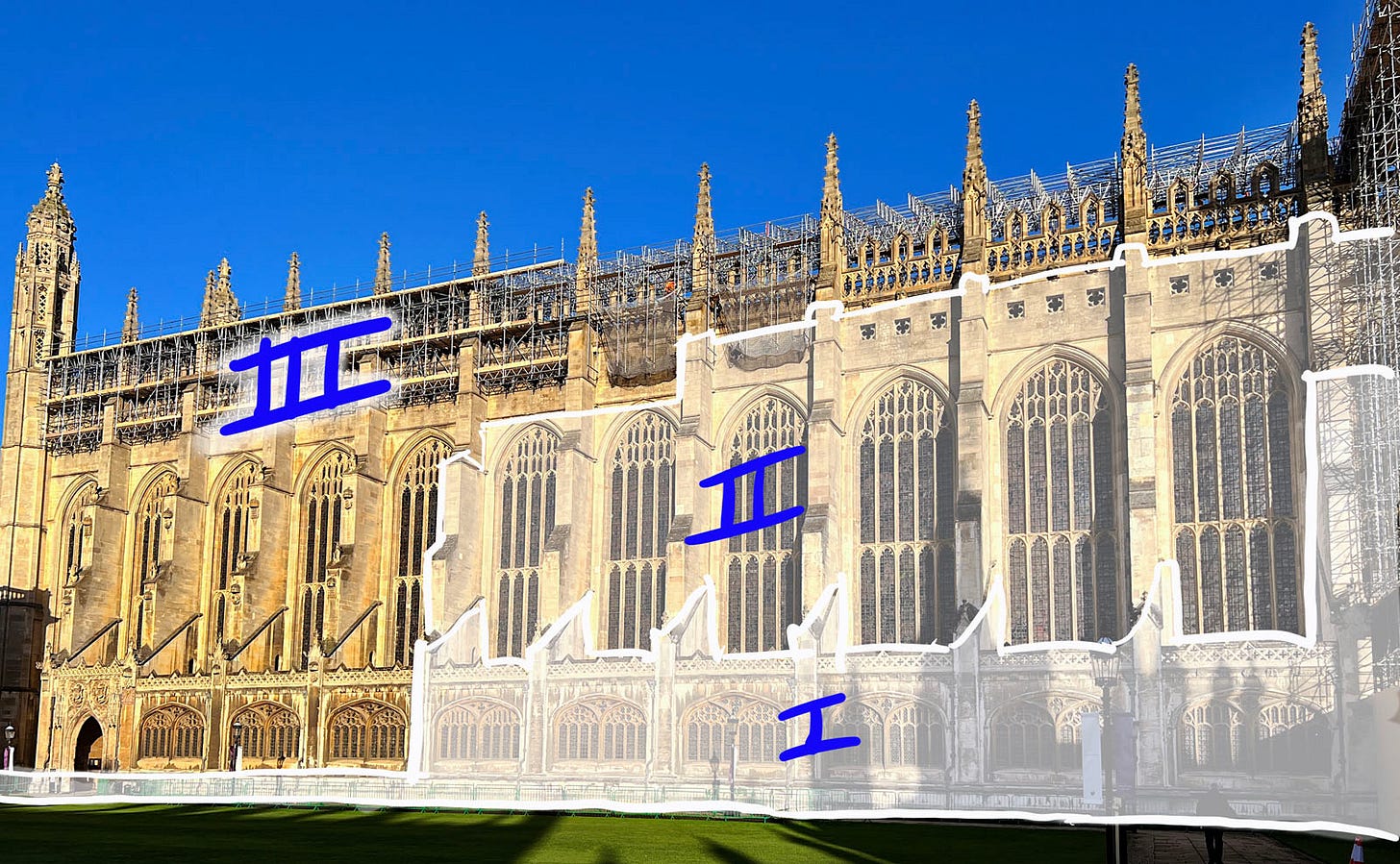

The Tudors were the new dynasty, and near the end of the reign of first Tudor king — Henry VII — construction recommenced. This final phase of building construction lasted from 1508-1515, and as Henry VII was succeeded by Henry VIII in 1509, two kings were involved in it. Figure 5 shows the the phasing on the south side of the chapel, which can be seen in subtle changes of stone color and design details if you look closely in person.

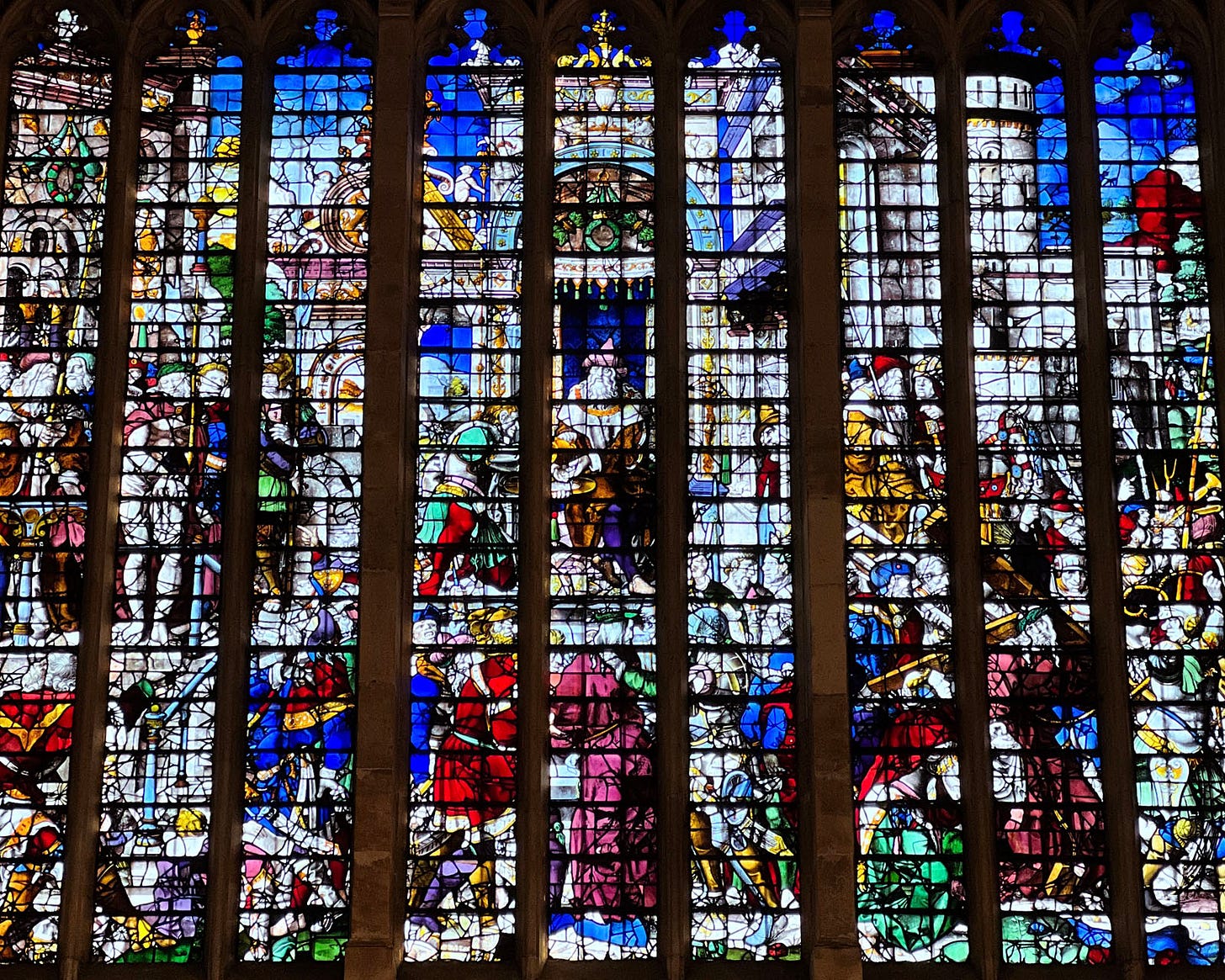

While the architecture was complete in 1515, the stand glass windows were not installed until 1531, in a Renaissance style (figures 10, 12-13 below). The Italian Renaissance style rood screen (figures 14-16 below) was installed from 1532-1536, in celebration of Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne Boleyn, which means that the final construction installations here occurred after England’s break with the Catholic Church. The building itself represents then, both in history and form, the shift from the late medieval world to the early modern one.

Photo Tour

As I mentioned above, King’s College Chapel is essentially just one big open space, so it’s pretty simple to explore. However, there are small side chapels along both walls which contain some nice medieval art and museum displays; we will look into those near the end of this photographic tour.

Figures 5-7 are all exterior shots, including a view from “The Backs” — a series of parks that run along the back grounds of a half dozen Cambridge colleges — and the west entryway.

Note the iconography above the door in figure 7, which is repeated, with variations, in the western interior bays (figure 8). This visual program was designed under Henry VII, founder of the Tudor dynasty, whose dynastic claim to the throne was tenuous.

The heraldic shield of England and France in the center of figure 8 ties him to the previous Plantagenet rulers. To the left of it, the Red Dragon of Wales references his Welsh ancestry and the banner he carried at Bosworth. To the left, the white greyhound and portcullis are emblems of the Beauforts.

These motifs are very much about legitimatizing the Tudors’ royal authority and shaping collective narrative through the medium of architecture — a subject which I happened to discuss three days ago in my post about the nature of bodies politic and role of media.

Figures 9-10 below (and figures 1 & 4 above) are more architectural shots of the western portion of the chapel, and figures 11-13 below (along with figure 2 above) are overviews of the eastern portion.

Dividing the eastern and western portions of the chapel is the Renaissance rood screen and choir stalls, shown in figures 14-16.

After you’ve explored the main chapel space, the side aisles are worth visiting as well. Figures 18-21 show some of the art and exhibits on display in them. But first, note figure 17, which shows a set of small sculptures in the trim to one of the side chapels’ entries.

This is a good example of religiously motivated iconoclasm, which I am guessing occurred during either (more probably) the mid-16th century period of the Reformation or (possibly) the mid-17th century English Civil War. While religiously motivated iconoclasm sometimes destroyed entire works of art, it was often considered enough to just (literally) deface it. Iconoclasm was rampant in certain countries during the Protestant Revolutions, and was the physical manifestation of the 16th century destruction of the medieval social order, a subject that I will discuss in my post this upcoming Wednesday.

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Date: 25 November 2022

King’s College Chapel is inside of King’s College in Cambridge, which is restricted to the public. Entry requires a ticket and occurs through the King’s College Great Gate, which leads you into the Front Court and along a restricted path to the chapel’s south entrance.

I am not sure how crowded this gets — I visited on a weekday in November and arrived when it opened, so it was pleasantly quiet while I was there. But you can purchase tickets online in advance and simply show them on your phone to the guard at the gate. Between the main chapel space and the historical information in the side chapels, you could easily spend up to an hour in here.

Cambridge has much to offer, so it’s not a bad idea to turn a visit here into a multi-day trip. In addition to wandering the town and colleges, the Fitzwilliam Museum is certainly worth an afternoon and/or morning; and if you are into church architecture, both the 12th century Round Church and Great St Mary’s (built about the same time as King’s College Chapel, though decidedly less spectacular) are very close by and worth popping into. And little Kettle’s Yard is a hidden gem of a museum if you like modern art and can manage to get in — hours are irregular and tickets very limited.

King’s College Chapel is an extraordinary testament to both architectural ambition and historical narrative. Its soaring vaults, intricate iconography, and historical significance make it a must-visit for anyone exploring Cambridge, and worth a special trip to Cambridge if you are into Gothic archiecture.

I attended a choral evensong service (same as Roman Catholic Vespers—but with trained choristers) in 2015. Absolutely magnificent! Both the architecture and the service itself. Recommended to those who like music, whether religious or not.

Nothing about the choir? Nothing about the organ? The Chapel is more famous for these than the fan vaulting.