(8 min read) Beauvais Cathedral represents all the runners-up to my top fifty list, and also exemplifies what could happen when medieval builders became too ambitious.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Beauvais Cathedral

Official Name: Cathédrale Saint-Pierre de Beauvais (Cathedral of St Peter of Beauvais)

Location: Beauvais, France

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1225 to 1573

Why It’s Great

At 48 meters (156 feet), the vaulting in Beauvais Cathedral is the tallest Gothic vaulting in the world: its interior height even surpasses St Peter’s in Rome, the Pope’s cathedral. Unfortunately — and relatedly — the church was never completed and has had structural issues from almost the beginning.

Why It Matters: History and Context

My survey of the fifty greatest works of Gothic architecture is beginning with an unexpected #51. This is in part to point out the arbitrariness of cutting off such countdowns at a specific round number, but also to recognize that there are a dozen or more runners-up I’ve documented which could arguably be placed in this list.

Of all the possible runners-up, though, Beauvais Cathedral is the best choice to showcase. That’s because — in a slightly different world — it could have been in the top five.

From the start, Gothic architecture was ambitious. In a world with no mathematical engineering (or even Arabic numerals), opening up stone walls with big windows and increasing the height of spaces was a tricky endeavor, bound to result in the occasional structural failure. But Gothic architecture was particularly ambitious during its initial stages, and this was especially the case in France.

There was a veritable boom in new cathedral construction from the mid-12th to early-14th centuries, and this boom exacerbated the potential for structural issues. That’s because every bishop who instituted a new building program felt compelled to outdo his fellow bishops and their slightly older cathedrals. Larger and more impressive designs were prioritized, and height was one of the most obvious means by which to make one’s cathedral stand out as the “best.” (This obsession with height was primarily a French thing, it did not affect the English cathedrals going up at the same time.)

Initial work on Beauvais’ Gothic cathedral began in 1225, and within 15 years they were ready to begin construction of the choir/chancel. At that time, Amiens Cathedral was slightly further along in construction and its interior had a height of 42m (139 ft), having beat out Bourges Cathedral for the title of tallest vaulting. Before that, Bourges had surpassed Reims, which itself exceeded the earlier Soissons, and so on, with Chartres and Paris being two of the earliest contenders in the competition for height. But in such a contest, and without modern engineering methods, it was virtually inevitable that things will get pushed too far.

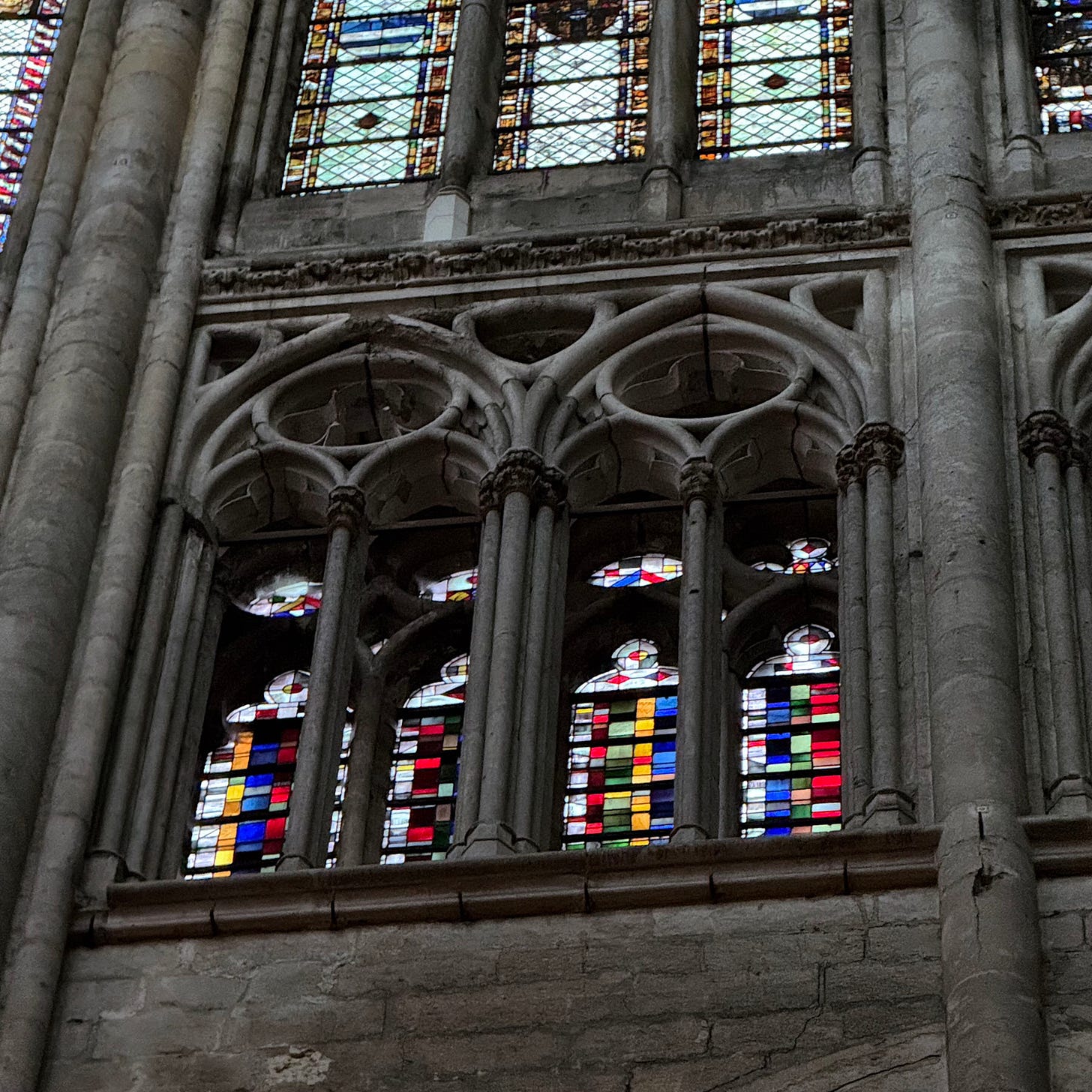

The choir at Beauvais was consecrated around 1260. Not only had they made the tallest space in the world, but it was also exceptionally light-filled, with wide bays and huge windows. You can see it today almost as it was then, and it is indeed awe-inspiring in its height and verticality:

In 1284, however, things started going wrong for the cathedral. That year a flying buttress twisted and broke; when it collapsed, so did much of the choir vaulting. The builders were undeterred, however. Over the next few decades, instead of continuing with construction of the rest of the church, they rebuilt the choir at the same height (though instituting a few structural adjustments).

With the choir finally re-built in the early 14th century, it was time to move on to the rest of the church. This cathedral was planned not just to have the tallest ceiling in the world, but also the longest and one of the widest naves.

But such grand ambitions take time, and soon financial issues, the Hundred Years’ War, and the Black Death all put a long pause on construction.

Major work didn’t resume until 1500, with the transepts. The builders also managed in this phase to construct the tallest tower in the world, with a crossing tower in 1569 that reached 153m (502 ft). It, too, was overly ambitious and fell in 1573, never to be rebuilt.

In fact, after 1573 little new work was done in terms of expanding the building, though preservation work and expenses associated with solving ongoing structural issues has been nearly constant. It still sits today as a nave-less stub of a cathedral — it’s a magnificent stub, don’t get me wrong. But between being unfinished and having so much ongoing structural repairs, visiting it is inevitably something of an anticlimax, especially when one knows what might have been.

With that in mind, let’s do a little “virtual tour,” based on my visit from just a few weeks ago.

Photo Tour

Figure 4 above is a view from the southwest looking towards the crossing and transepts. The small building where part of the Gothic nave would have been located (lower left) is the 10th century Carolingian church. It is connected to the interior of the cathedral and still in use.

Walking around the church clockwise from here (figures 5-7), you can examine the transepts and the choir from the outside.

The south transept has a lot of scaffolding around it so I have not shown it. But we enter the church from here — and doing so will show you exactly why, no matter how magnificent the choir is, I cannot consider Beauvais Cathedral a contender for a “Greatest Fifty” list.

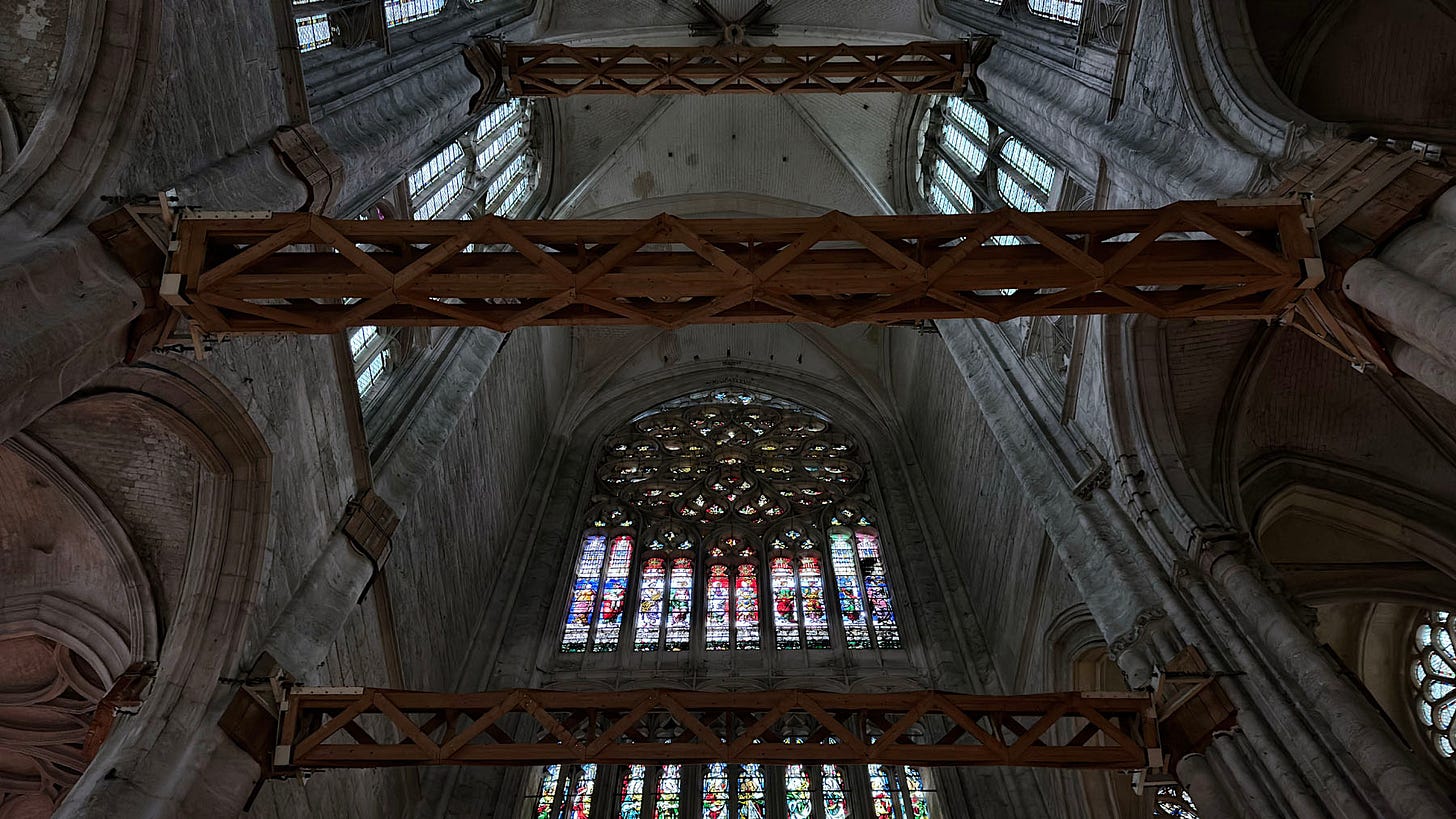

Figures 8-10, along with figure 2 above, show that the original builders’ success was not only partial, but essentially temporary and incomplete. It seems unlikely to me that most of the bracing visible today will be removed in the foreseeable future, if ever.

Still, we can enter the chancel/choir and appreciate what might have been (figures 11-14).

As I mentioned above, when the choir was rebuilt after its partial collapse in 1284, a number of structural changes were made. Most significantly, the wide bays along the straight sides were halved in size with the addition of new columns, making them about the same size as the apsidal bays. In the lower section of figure 15 below, you can make out two of the original large arches — they now have a new column running through them and two smaller arches; the remainder of the original arch openings have been filled in.

In addition to the choir/chancel, the original 13th-14th century ambulatory and many side chapels can also be visited. Figures 16-20 show the ambulatory itself followed by some of the radial side chapels.

A few other side chapels located near the transepts are also worthy of note and shown in figures 21-24.

St Angadreme was a 7th century daughter of Merovingian nobility, and is now Beauvais’ patron saint. She became a nun and founded an abbey a few miles away. The sculpture in figure 22 is of her, and the mural in the background shows a 15th century miracle associated with her remains and reliquary.

This concludes the photographic tour, but check out my instagram page today and tomorrow to see some additional photos from here.

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Date: 17 December 2024

The town of Beauvais is small and finding parking is easy; if you take a train, the cathedral is just a ten-minute walk from the station. Entrance is free, though donations are welcome.

While “highest Gothic vaulting in the world” is a draw for many, overall the experience the cathedral affords is underwhelming and almost melancholic compared with other Gothic landmarks.

Beauvais Cathedral today offers a glimpse of what could have been the most magnificent Gothic structure in the world. Its soaring choir remains an awesome achievement—a testament to the ambition, ingenuity, and faith of its creators. But its incomplete state, and the abundant scaffolding and bracing that surrounds and fills much of the church, remind us of the challenges faced by medieval builders in their quest to transcend earthly limits.