(10 min read) In addition to being a stunning building, Budapest’s Matthias Church — number 50 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — is a fascinating case study in questions of authenticity and national identity.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Matthias Church

Official Name: Nagyboldogasszony-templom (Church of the Assumption of the Buda Castle)

Location: Budapest, Hungary

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1255-c1500 & 1874-1896

Why It’s Great

Matthais Church in Buda Castle is Hungary’s most important Gothic landmark, a masterpiece of multiple reinventions that embodies the country’s complex history and sense of identity.

Why It Matters: History and Context

Tradition says that Matthias Church was founded by King Saint Stephen, the first hing of Hungary, in c1015. The Romanesque church he founded was destroyed by the Mongols in 1241.

In 1242 the Mongols retreated due to internal strife, allowing King Bela IV to rebuild Hungary’s infrastructure, including the first Gothic iteration of Matthias Church. Under his leadership, the earliest Gothic architecture was built in what is now Hungary — a three-nave basilica was built from 1255-1269.

In the second half of the 14th century, the church was rebuilt in a more mature Gothic style with a nave and two side aisles. Included in this redevelopment was the Mary Portal (figures 4 & 13); it was constructed in 1370, a hundred years after the completion of the initial Gothic church, and one of the few artistic from this period to survive intact through to today.

Another hundred years later, in 1470, the south tower — which had collapsed in 1384 — was rebuilt under King Matthias I (also known as Matthias Corvinus). Matthias also began a northern tower and built a royal oratory nearby; the construction he spearheaded was important enough that the common name for the church is now Matthias Church, and his heraldic emblem, the raven, can be seen in various parts of the church like the exterior towerettes and interior stenciling (figure 5).

The Ottoman Turks, under the leadership of Suleiman the Magnificent, took over Buda in 1541. In the same year they converted Matthias Church into a mosque, destroying much — but not all — of the building fabric in doing so. The Ottomans ruled Buda and (much of Hungary) for some 150 years: it wasn’t until 1686 that Buda was retaken by Christian forces.

Soon after, the Jesuits took over the church. They made it part of a larger building complex and renovated it in a Baroque style, causing much of the medieval ornamentation to be lost. The Jesuit order was dissolved in 1773, and the buildings then languished under the ownership of the council of the city of Buda.

Starting a hundred years later, though — in 1874 — a major rebuilding took place under the auspices of Franz Joseph I of Austria and the architect Frigyes Schulek — and under the influence of the 19th century’s nationalistic movements. These reconstructions, which lasted until 1896, resulted in the church as we see it today:

These reconstructions also raise a couple of interesting questions about authenticity, which are best represented by figures 6 & 7. Figure 6 shows the exterior of the church from the south. Virtually all of this was rebuilt in the 19th century, according — as much as possible — to the medieval structure. And figure 7 shows the nave, narthex, and side aisles inside — all covered in an exuberant riot of Jugenstil-inspired patterns and paintings.

The first question is best introduced by way of the philosophical paradox called the Ship of Theseus, which asks whether an object is the same if all of its parts are replaced. (Read the italicized and bracketed text below if you are not familiar with it.)

The Ship of Theseus: When Theseus returned from his Cretan adventures with the Minotaur, the Athenians decided to preserve his ship. Over the centuries, as various planks and components decayed they were replaced by new ones. Eventually none of the original components remained, raising a question among the philosophical Athenians — was this still the same ship?

The same question can be raised about you and your body: odds are very high that none of the molecules (and virtually none of the cells) in your body are the same as those that were there a decade ago. Do you still have the same body?

I am fairly certain that no objects exist in any deep, eternal, metaphysical sense (a position held by process philosophy along with several other schools of thought). Rather, the universe is a patterned flux of eternal becoming. So I have no problem saying the ship or your body is the same from one century or decade to the next in so far as the “materials” that comprise it follow the same patterns of being. But there are plenty of intelligent people who disagree with me.

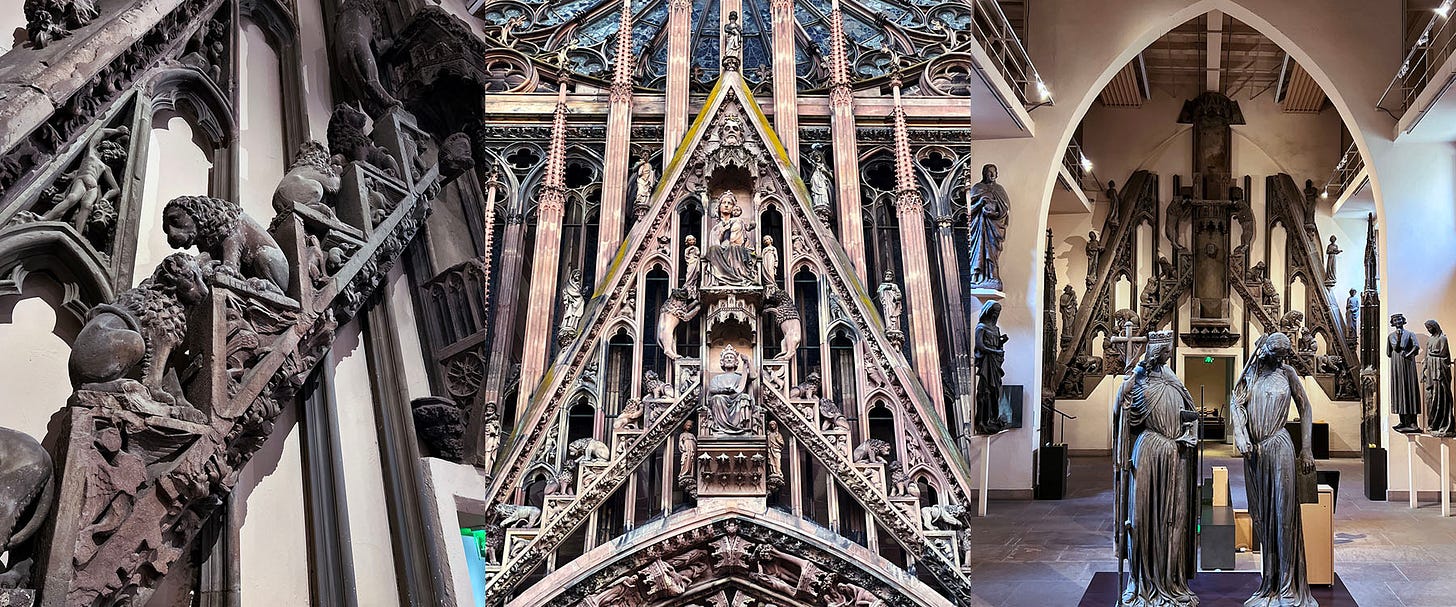

Given the amount of restoration and rebuilding that happens with thousand-year-old churches, this paradox relates to virtually all Gothic architecture. To take one very specific example: the sculptures currently in the portals at Strasbourg Cathedral are faithful copies, with the originals in a museum across the square (figure 8).

The Strasbourg example could be repeated across virtually any Gothic building; very few of the originally installed sculptures, gargoyles, etc still exist on most of them, and in many cases a lot of replacements have happened — a flying buttress here, a door there, etc. But it’s still the same cathedral, right? And authentically Gothic? I would say so.

Matthias Church is an extreme example, however. As you might guess from the storied history I outlined above, not a lot of the medieval building fabric still remains. Even Matthias’ tower was completely rebuilt during the late 19th century reconstructions. However, the architects working on these reconstructions had good drawings, descriptions, and many original building components to work from, allowing them to make a darn faithful copy of the building as it existed around the 15th-16th centuries.

While one could argue that so much reconstruction has happened that the church is now a “Gothic revival” building (a style I am not including in this countdown), I say it is still Gothic proper.

At least on the outside; the inside is another matter.

While Schulek and the artists involved in the late 19th century rebuilding of Matthias Church maintained a faithful approach on the exterior of the building, they got radical with the interior. At the same time, this “radical” approach was appropriate both to the history of the church, with all of its radical reconstructions over the centuries, and to the historical moment they were in.

The 19th century was the age of nation-building across all of Europe, but the process held a special urgency in Central Europe, where diverse ethnic and linguistic groups coexisted with differing histories.

A lot of factors fed into the process of creating nation-states in the 19th and 20th centuries, and the process was far too complex to discuss in detail here. But one key element everywhere was the creation and propagation of new “national identities” through shared historical narratives and art that reflected these stories. This was the period of collecting folk and fairy tales, for example, and reassessing older art and architecture.

In the earlier part of the century, the Gothic Revival in France and England played a key role in this cultural movement. By the later 19th century, it had spread across Europe and evolved into related movements like Arts & Crafts (England), Art Nouveau (France & Belgium), Modernisme (Spain), Jugendstil (Germany, Bohemia, and many Slavic contries), and Secessionism (Vienna).

So — just as Stephen I founded a church on this site, and Bela IV added a royal oratory, and Matthias Corvinus made his mark — Frigyes Schulek and his team of artists turned Matthias Church into a national symbol, an embodiment of the new national consciousness that was then becoming the Hungary we recognize today.

I think it is time now that we took a closer look at exactly what they created, with a short photo tour of the place.

Photo Tour

Over the course of my historical survey, we got a good look at the exterior of Matthias Church (figures 2-6 & 9). Figures 11 & 12 show the west facade and its portal.

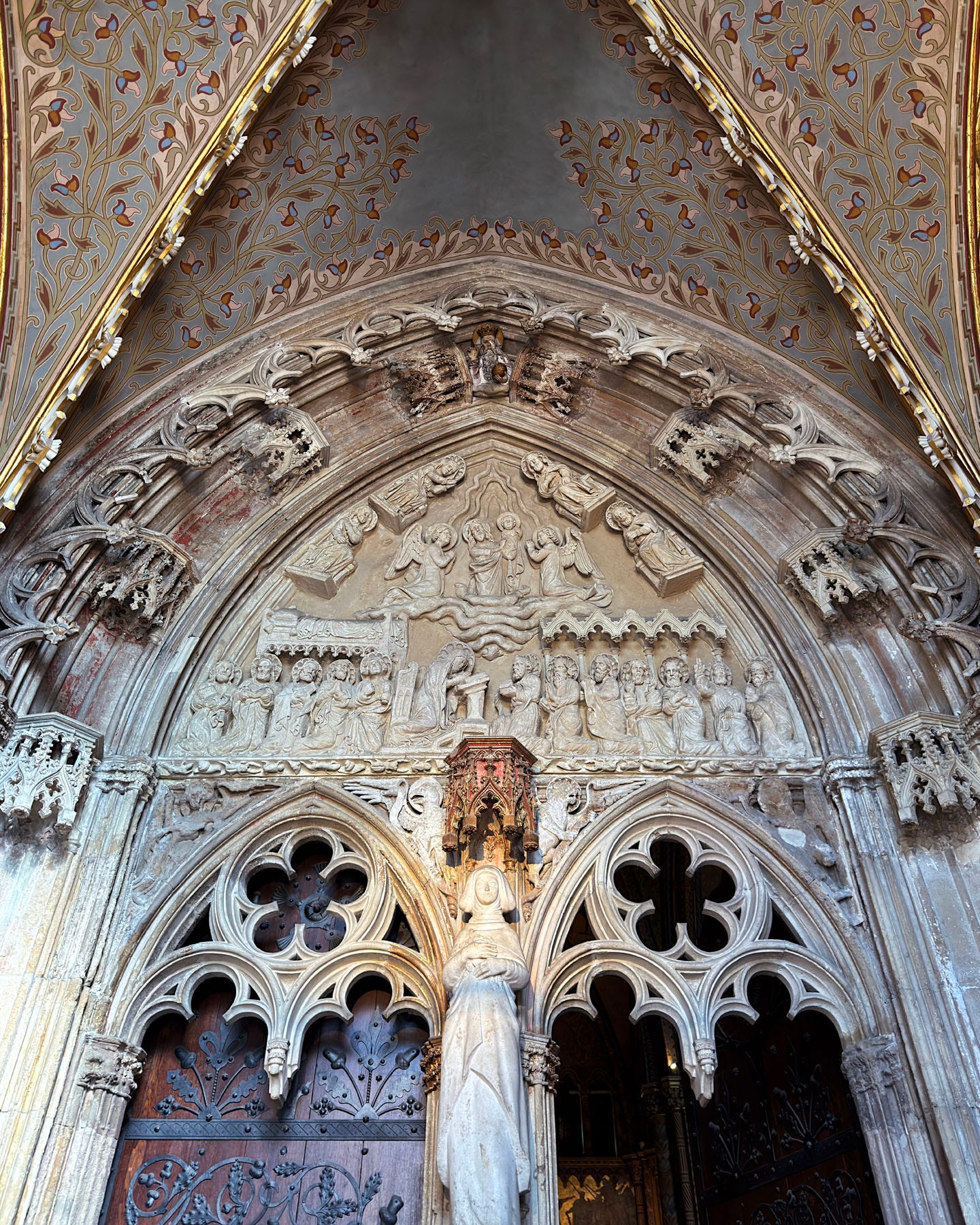

The entrance today (figure 4) is on the south side of the cathedral near the tower; we enter an enclosed porch which includes the 14th century Mary Portal (figure 13), one of the few pieces of original medieval sculpture that remains.

Another rare survivor is the central section of a clustered column capital (figure 14), which dates from 1260 and is still located in its original position near the narthex and baptistry.

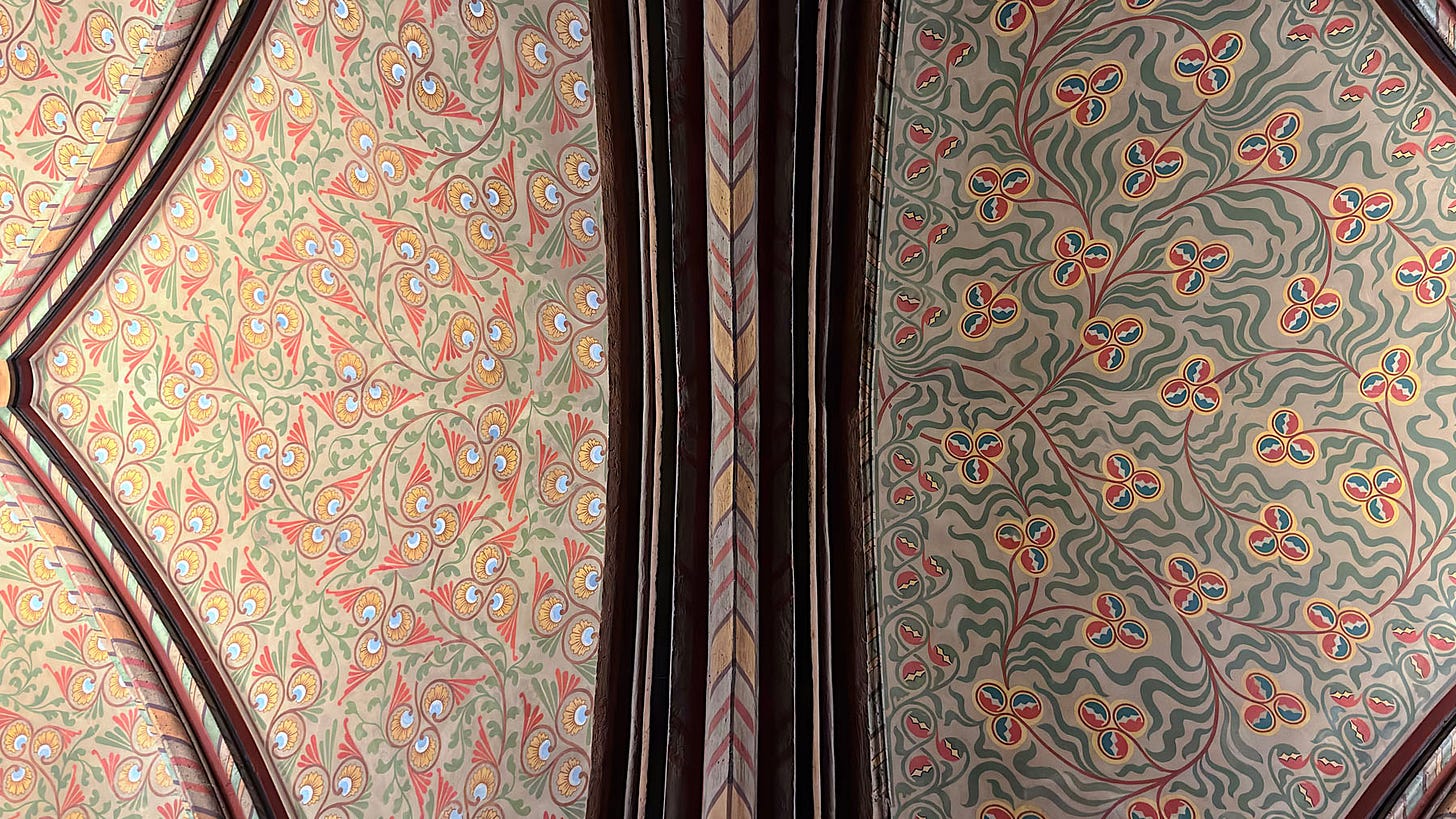

The narthex and baptistry (figures 15-17), with their low ceilings and more intimate feel, are also a good place to get a close look the incredible stenciled patterns and integrated artwork that fills the entire church.

The baptistry (figure 16) is a good example of the integration of art and architecture, with a stained glass window showing the Lamb of God, from which the Waters of Life flow (visually) into the Neo-Romanesque font.

The two different three-lobed patterns in the vaulting at the narthex and baptistry (figure 17) are very reminiscent of the cintemani motif, which was a popular design motif in the Ottoman Empire during the periods the Turks controlled Buda (in fact, you can still readily find it today in Istanbul). If this was an intentional borrowing (and I suspect it was), it shows how the design ideas incorporated into the church reflect all of Budapest’s complex history, even the non-Christian aspects.

Figures 1, 7 & 18 show the nave and side aisles, and figures 19-20 showcase the choir and high altar.

The north side of the church now contains several side chapels — some of them built in the 19th century, some in the original church fabric — which include historical relics as well as murals with historical narratives painted on the walls. Figures 21-23 show three of them.

The north side of the church also includes a small museum (figure 24).

Finally, if you are reasonably fit, it is certainly worthwhile to climb the 197 steps of the tower and take in the magnificent views of Buda Castle and the Pest side of the city (figure 25).

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Dates: 7 & 8 October 2024

Matthias Church is a popular site and charges an entrance fee, so I suggest both arriving early and purchasing your tickets online. Visiting the tower requires a separate ticket with a timed entry.

It is next to Fisherman’s Bastion, which was redeveloped in the 19th century shortly after the church, according to Schulek’s plans and a Neo-Romanesque design. The Bastion offers great views of Budapest in a romantic setting and accordingly gets very crowded with selfie-takers, especially in the early morning and late evening.

Matthias Church is also part of the sprawling Buda Castle complex, which includes a lot of museums and opportunities for other touristy activities. Plan to make a whole day out of your visit to the area if you are staying on the Pest side of Budapest, or perhaps even — like me — two full days.

Matthias Church is not an obvious contender for my Gothic Top Fifty survey, but it is certainly the most important Gothic building in Hungary and if — like me — you enjoy Art Nouveau architecture almost as much as Gothic, then you will find yourself gobsmacked by the intensity of the interior.

That high altar tho 🤯