Greatest Gothic, #44: Basilica of St Francis of Assisi

The Frescoed Heart of a Medieval Movement

(9 min read) The Basilica of St Francis of Assisi — number 44 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — stands as a monument to the important movement and Order that St Francis initiated, with gorgeous interiors that showcase Italian frescoes from the 13th and 14th centuries.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi

Official Name: Basilica di San Francesco d'Assisi (Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi)

Location: Assisi, Italy

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1228-c1350

Why It’s Great

The Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi is a unique Gothic structure, blending Romanesque solidity with Italian Gothic elegance while also serving as a monumental shrine to one of Christianity’s most influential figures. Its fresco-covered interiors, executed by some of the finest artists of the 13th and 14th centuries, make it as much an artistic masterpiece as an architectural one, capturing both the humility of St. Francis’ message and the grandeur of the movement that followed him.

Why It Matters: History and Context

The most famous saint of all time, Francis of Assisi, died in 1226 and was canonized just two years later. His order immediately began constructing a basilica in his honor, and by 1253, the main structure was complete. The speed with which the basilica was planned and built is striking for the 13th century.

Pope Gregory IX (who canonized Francis) personally laid the foundation stone in 1228, just two years after Francis' death—an unusually swift response, even by medieval standards. This level of papal endorsement reflected the Church’s sense of urgency in aligning itself with the Franciscan movement—both to harness its immense popularity and to prevent it from evolving into a breakaway sect. As I mentioned in my post ten days ago, the Franciscans were a rare example of the medieval Church co-opting a radical movement rather than claiming it to be heretical and executing its leader.

Though St Francis might not seem radical today, he most certainly was. Like a medieval Crates, Francis was born into a wealthy family but renounced his inheritance, choosing a life of radical poverty and itinerant preaching. His embrace of simplicity and service — not just as a personal discipline but as a direct challenge to the materialism of both secular and ecclesiastical elites — made him an unusual and disruptive figure in the medieval world.

There’s an inherent contradiction in Christianity as a political movement, especially when it takes on state-like functions, as it did in the Middle Ages (and as certain disturbingly powerful Christian Nationalist movements in the US would like to have happen again).

One of the saving graces (pun intended) of Christianity as an organized religion, it seems to me, is that its founder had no interest in worldly power and preached a radical inversion of social hierarchy. Francis followed that example with his call for poverty — not just as personal virtue, but as a challenge to the Church’s entanglement with wealth and authority. That tension, between a faith based on renunciation and an institution embedded in power, lasted throughout the Middle Ages and continues through today, ensuring that movements like Francis’ will always re-emerge, calling the Church to account.

Such tensions are made visible in the architecture here. On the one hand, the exterior (figures 2 & 14-15) largely reflects the austerity expected from a monastic order devoted to apostolic poverty. On the other hand, the lavish frescoes and grandeur of the interior—not to mention the sheer scale of the basilica itself—speak to the immense popularity (and inevitable institutionalization) of the Franciscan movement. This paradox continues to the present day, evidenced most strikingly by the current pope taking the name Francis despite being a Jesuit.

While, as mentioned above, the main structure was complete in 1253, fresco decoration continued for decades, and noble patrons funded the addition of side chapels in the Lower Basilica from 1270 through about 1350.

Assisi is a classic Umbrian hill town, and the basilica complex sits dramatically at its western edge (figure 2). This location required the church to be oriented in a manner that is high unusual: instead of the apse and high altar being on the east side and the main entry and facade on the west, which is standard (see this post), here the church is oriented with its main entrance to the east and the apse and altars are on the west side.

In addition, the steeply sloping site necessitated a three-tiered structure: at the lowest level is a small crypt housing the remains of St. Francis (figure 5). Above that is the Lower Basilica, whose nave retains Romanesque proportions but whose later additions, including its side chapels, are Gothic. Resting atop it is the much larger Upper Basilica, which is accessed separately and functions as a distinct space.

We’ll begin our photo tour in the Lower Basilica before moving upward to the grander and more light-filled Upper Basilica. Photography is not permitted in any of the interior spaces here, so my documentation is less extensive than normal — however, I think you will find that I managed to sneak enough shots to provide a pretty thorough feel for the interiors. (NB: Before you judge me for taking photos of sacred spaces where it is prohibited, note the monk taking a photo of St Francis’ shrine in the lower left corner of figure 5.)

Photo Tour

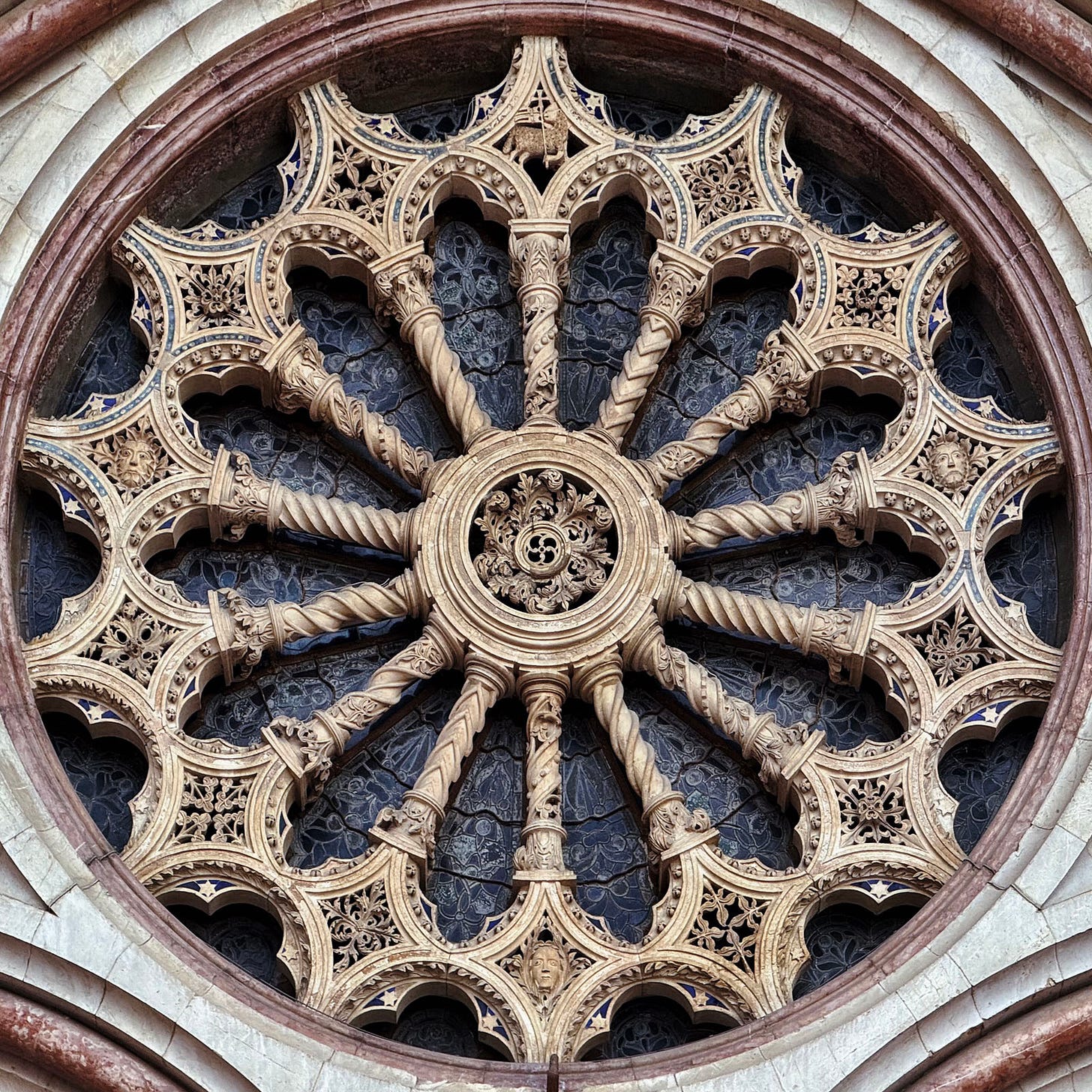

The Lower Basilica is entered through a south portal created between 1280 and 1300 in a wonderfully ornate Gothic style, and covered by a 15th century Renaissance porch (figures 6-7). Inside, the nave of the lower basilica (figures 1 & 7-9) feels like the undercroft it is, with thick walls and relatively low ceilings; on the other hand, the frescoes and painted designs which cover most of the walls and vaults offset the crypt-like feel with intense colors and storytelling.

While there are no side aisles here, the nave is lined with side chapels on both sides which have passages both from the nave and between them (figures 4 & 10-12). Being more narrow than the nave, the spaces become more vertical, with Gothic ribbed vaulting. While many of the chapels’ frescoes have deteriorated over time, the Chapel of St Martin of Tours (figures 11-12) stands out for it cycle of beautiful and very well preserved frescoes by Simone Martini, made from 1313-18.

The west end of the Lower Basilica offers entry to the part of the monastic complex that is open to the public, including a large patio and two-story cloister (figure 13).

Depending on the time of day, a back entrance to the Upper Basilica from the cloister may be open as well. But to properly appreciate this space it is best to approach it from the town side to the east (figures 14-15).

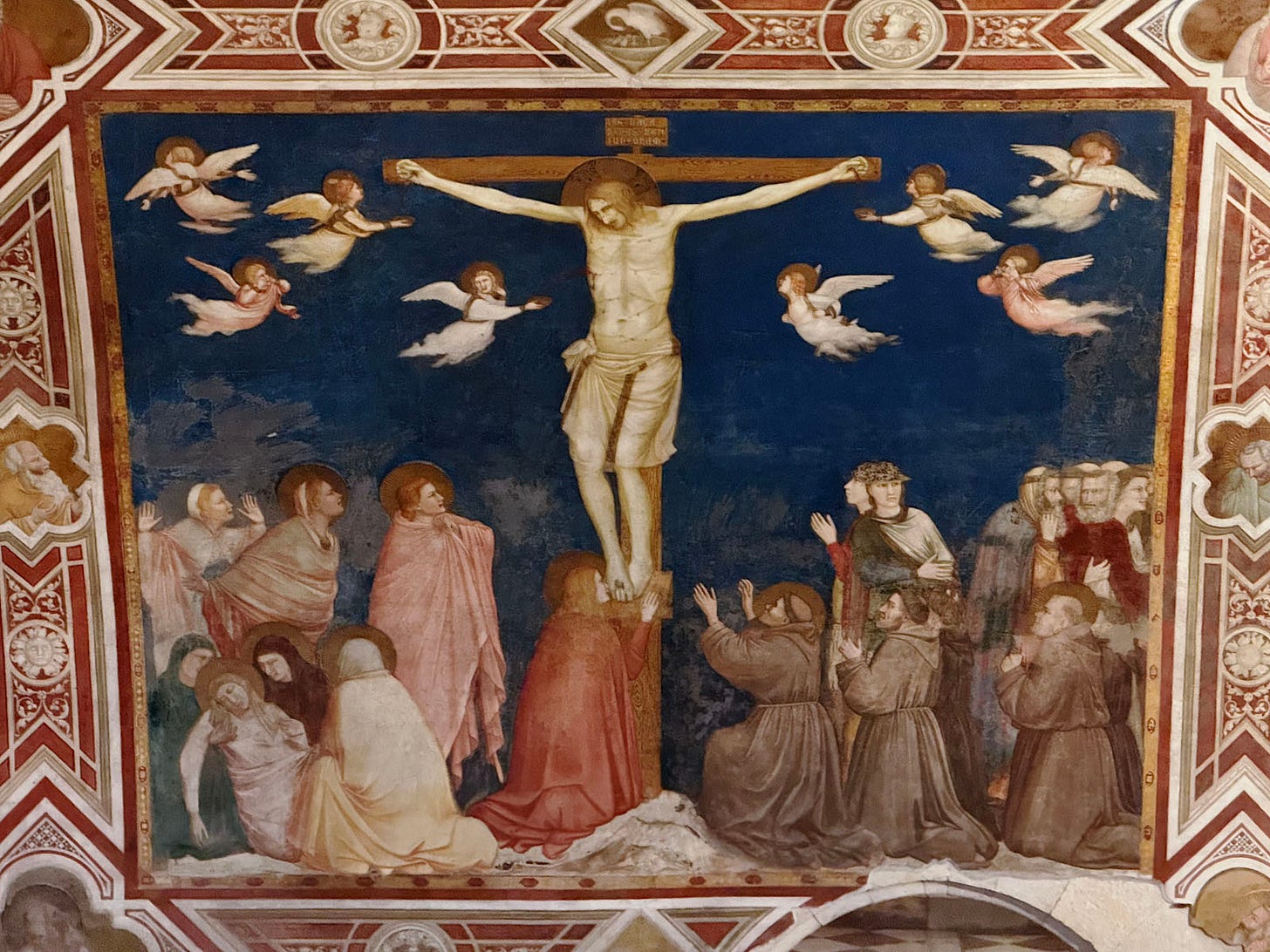

Entering the Upper Basilica through the west portal, you take in a tall Gothic nave with a crossing, transept, and apse at the far end (figure 16). While the lancet windows are smaller than in most Gothic architecture, the vivid frescoes that fill the walls serve much the same purpose and reflect one of the stylistic features that distinguishes Italian Gothic from that of all other regions (figures 17-20). While the main frescoes here were once attributed to Florentine Giotto di Bondone, scholars now question his authorship; Regardless of the painter, however, they are incredibly impressive.

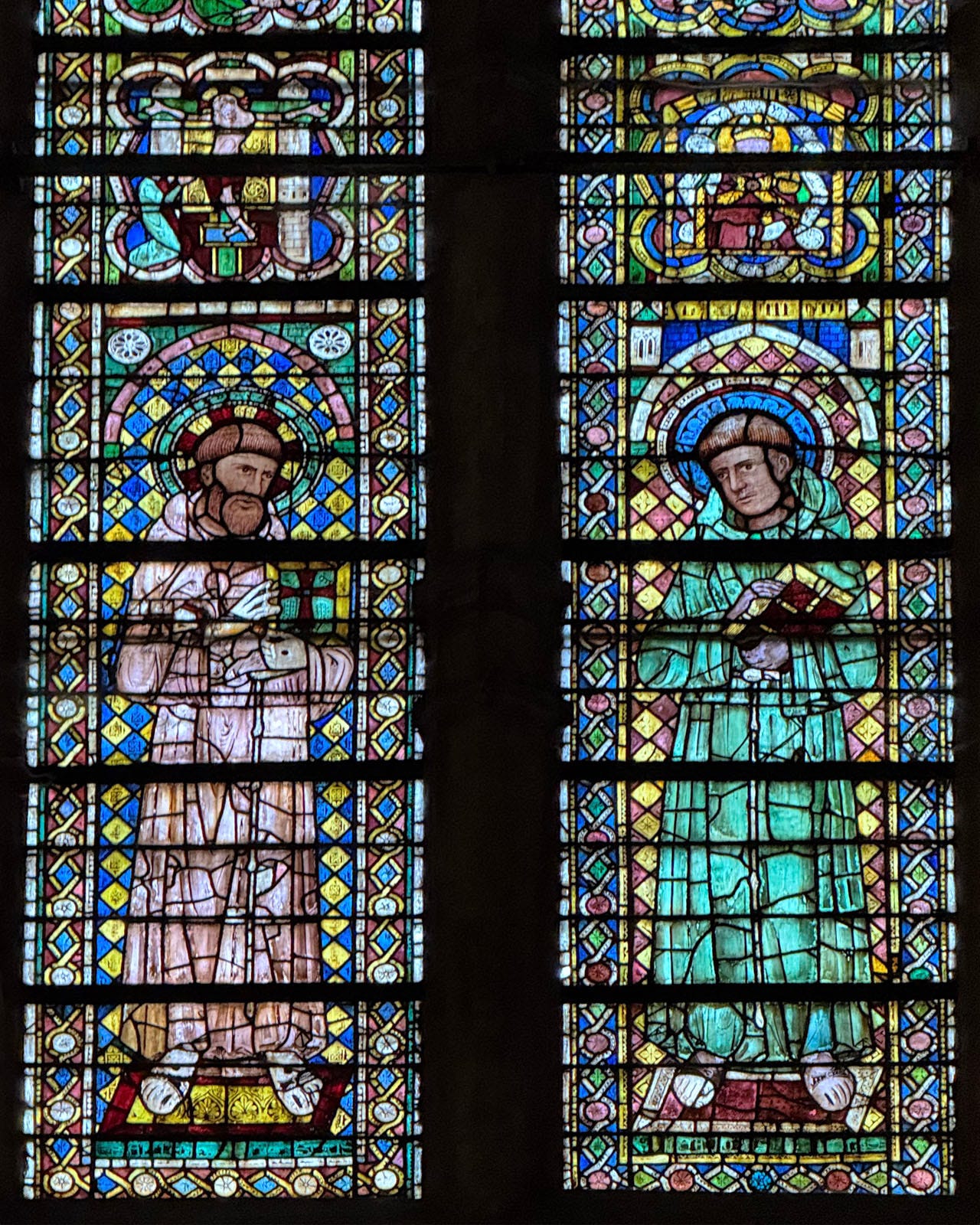

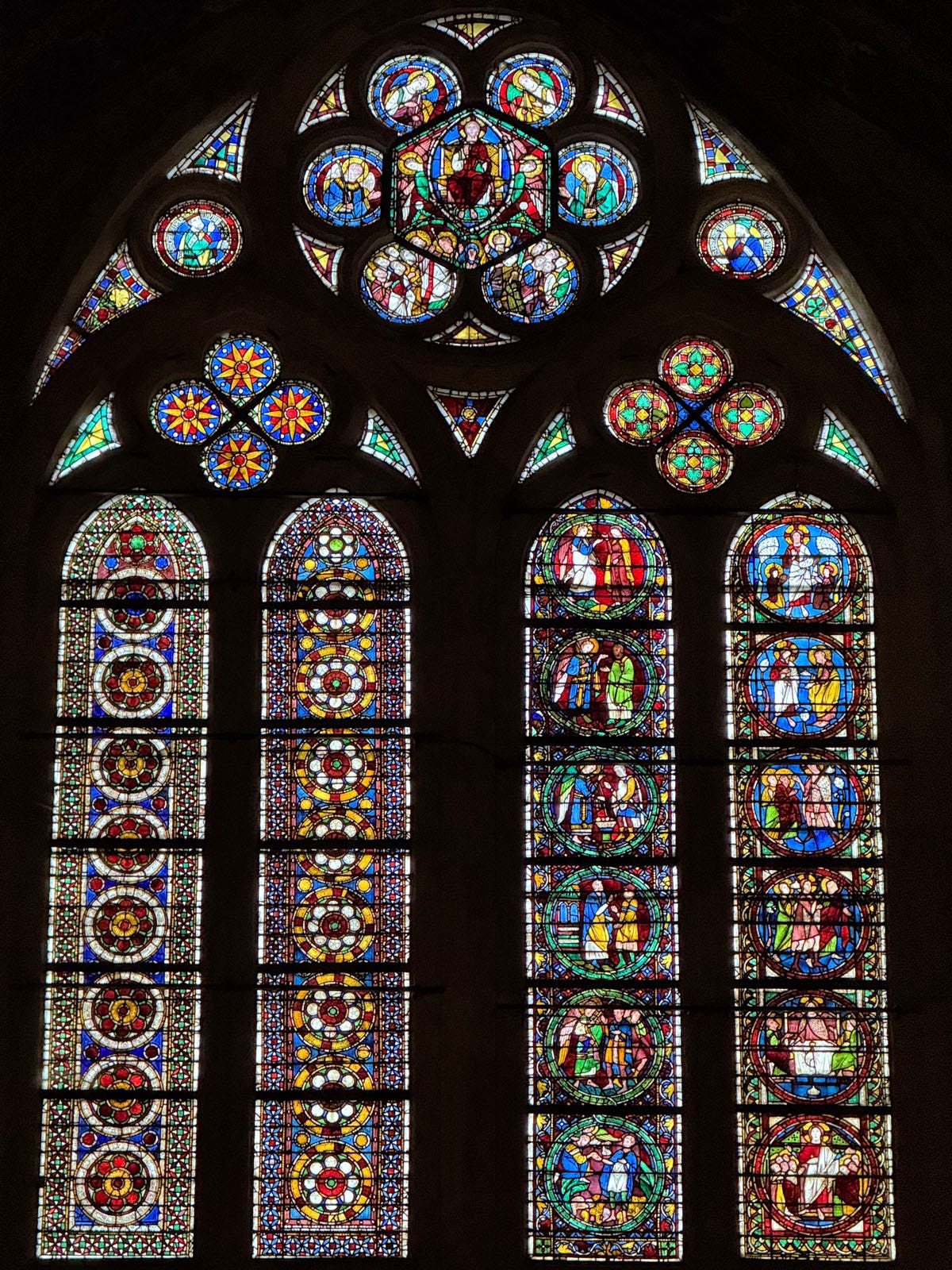

The west end of the Upper Basilica has a crossing with an altar, two transepts and a simple semi-circular apse (figures 21-25). The largest stained glass windows in the church are those at the ends of the two transepts (figures 23-24). Like the nave, they are filled with stained glass from the late 13th century — the colors of glass here are much lighter than most medieval stained glass, which become a vibrant pastel with good sunlight.

Unlike most Gothic churches of this size, there is no chancel to speak of before the apse, and so the choir stalls here also line most of the transept walls (figures 25-27).

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Date: 14 November 2024

Assisi is an incredibly popular destination for day trippers, so arrive early — or spend the night — if you want to avoid busloads of people being herded around both the basilica and the town itself. While there are not as many sights and museums as some nearby hill towns, like Orvieto, the Cathedral of San Rufino at the opposite (east) end of of town is worth visiting if only for its well-preserved Romanesque facade.

For all its contradictions — Franciscan simplicity housed in an opulent, papally-sponsored sanctuary — the Basilica of St Francis remains one of the most profound architectural statements of medieval Europe, both a contemporary pilgrimage site and a masterpiece of Italian Gothic where faith, power, and artistic ambition meet.

An excellent essay that reaffirms my need to prioritize a visit to Assisi on a future Italy itinerary. The photos you captured of the frescoes through the complex 😮💨 make my heart so, so happy! 🙏🙌

Beautifully photographed, and sensitively written. You have opened a visual and verbal treasure for us. Thank you.