(7 min read) Brussels Town Hall — number 43 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — is a spectacular example of non-religious Gothic architecture from the Middle Ages.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Brussels Town Hall

Official Name: Hôtel de Ville de Bruxelles/Stadhuis van Brussel (Brussels Town Hall)

Location: Grand-Place, Brussels, Belgium

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1401-1455

Why It’s Great

Anchoring Grand-Place — the city’s premier public square — Brussels Town Hall is the finest example of “Civic Gothic,” featuring elaborate Brabantine detailing, vast arrays of medieval sculpture, and many exceptional interiors in the Gothic Revival style. While the overwhelming majority of Gothic architecture is religious in nature, Brussels Town Hall shows that the same soaring ambition could be applied to secular buildings, reflecting the rising power and pride of medieval cities.

Why It Matters: History and Context

While the cathedral is the archetypal work of Gothic architecture, and the vast majority of Gothic buildings are religious in nature (they were built in the Middle Ages, after all), there are many examples of exceptional “Civic Gothic” buildings — town halls, guild houses, and some market buildings. These buildings reflect a broader shift in power during the High and Late Middle Ages, as cities grew into political and economic forces in their own right.

Flanders has a particularly rich tradition of town halls built during the Gothic era, and figure 3 shows three examples of various sizes. Urban centers in Flanders were among the wealthiest and most autonomous in medieval Europe, with powerful merchant and craft guilds often wielding as much influence as the nobility. As these cities gained independence from feudal lords, they constructed monumental town halls as symbols of their newfound political authority.

Brussels Town Hall is not only the greatest of the Gothic town halls — it is the greatest non-religious work of Gothic architecture, full stop. Towering over Grand-Place (figures 1, 6 & 11), it forms the architectural and civic heart of Brussels, a city that has since grown into the capital of Belgium and, in many ways, of Europe itself.

The construction of Brussels Town Hall took place in two major phases. The original left (east) wing and the lower portions of the tower were built between 1401 and 1421, under the direction of Jacob van Thienen. In 1444, work began on the right (west) wing and the soaring tower, designed by Jan van Ruysbroeck and completed by 1455. The asymmetry of the wings is a quirk of history — the right wing was added later to balance out the structure, but the off-centerness of the tower remains a distinctive feature.

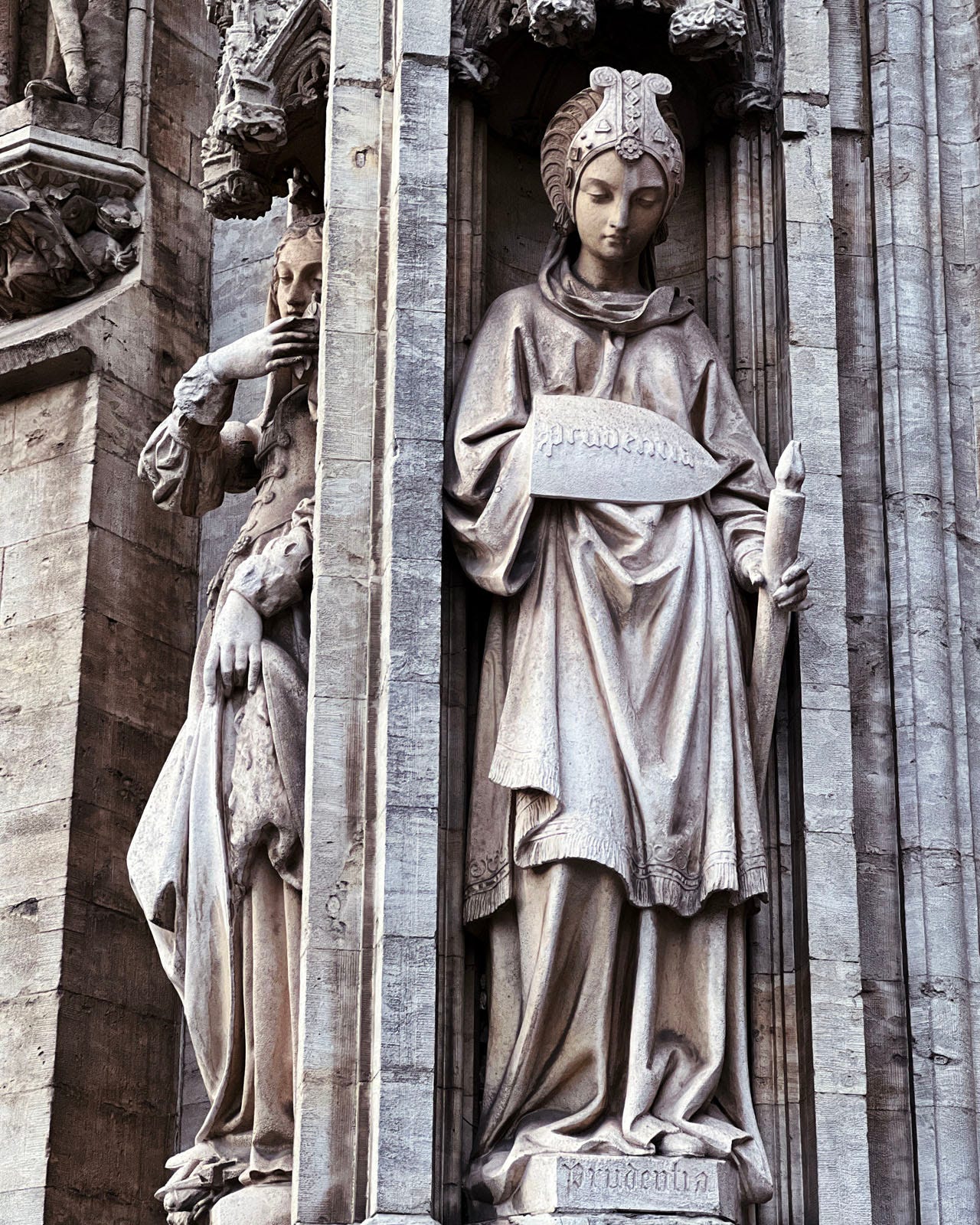

The exterior of the building is dominated by its Brabantine Gothic facade, densely packed with niches containing statues of dukes, duchesses, saints, and allegorical figures. Rising above it all is the tower, which soars to 96 meters (315 feet) and is crowned by a gilded statue of St. Michael, the patron saint of Brussels, triumphing over a dragon.

In August 1695, Brussels Town Hall suffered massive damage when French troops under Louis XIV bombarded the city during the War of the Grand Alliance. Much of the surrounding Grand-Place was reduced to rubble, and while the structure of the Town Hall remained standing, it was gutted by fire.

Reconstruction efforts began almost immediately, with the exterior being restored to its original medieval form. The surrounding square, however, took on a new character: the guild houses that surround Grand-Place were rebuilt in Baroque style, creating a visually striking contrast with the Town Hall. Today, this “new and improved” Grand-Place provides an incredible stage for viewing the Town Hall’s Gothic grandeur, especially at night (figure 7).

Photo Tour

The main attraction of the Town Hall is its exterior, which can be appreciated from Grand-Place itself, as well as some of the surrounding streets (figure 8). In addition to standing back and getting a sense of the whole facade and multitude of statues, getting up close and exploring the ground level details is very rewarding as well.

(Note that most statutes on the facade, and the St Michael statue atop the tower, are 20th century copies of 15th century originals — originals are held in the city museum across the square.)

The main portal, located at the base of the tower, is one of the most impressive in Gothic civic architecture. Flanked by sculpted figures and topped with a tympanum featuring St. Michael, St. Christopher, and St. George, it sets the tone for the artistry found throughout.

The arcades running along both sides of the tower provide another striking feature. The rib-vaulted ceilings are supported by corbels sculpted with scenes of daily life, including representations of medieval trades.

The east arcade includes an elevated porch with staircases to an old entry. Stone lions and readily visible pendants flank it (figures 19-21). One of the more intriguing sculptural details is a pendant depicting the legend of Herkenbald (figure 20), a medieval judge who was forced to execute his own nephew for rape. The theme — that justice must be impartial, even at the expense of family loyalty — was a not-so-subtle reminder to the aldermen and magistrates entering the building: duty to the law must come before personal or patrimonial interests.

The Gothic Revival interiors here date from the late 19th century, when Brussels undertook a massive restoration of the Town Hall. The “Wedding Hall” (figures 2 & 22-25) is particularly spectacular, with woodwork, sculptures, and painted panels depicting important figures from Brussels’ past.

The Gothic Room (figures 26–27) showcases tapestries and sculptures celebrating the city’s medieval guilds.

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Dates: 29-31 August 2022

Visit both day and night if you can because the place is magnificently lit after dark. To see the interior requires a guided tour, which — since times and spaces are limited — should be booked in advance, either online or at the Town Hall’s information office.

If you are interested in seeing the original sculptures or would like to learn more about the history of the Town Hall and Grand-Place, make sure to also pay a visit to the Brussels City Museum, which is conveniently located across the square in a wonderful Neo-Gothic building.

Brussels Town Hall is not only the finest example of Gothic civic architecture, but also the heart of one of Europe’s most breathtaking public squares. Whether admired from Grand-Place or explored through its richly detailed interiors, it stands as a testament to the political, artistic, and cultural ambitions of medieval Brussels—one that continues to command awe today.

Another fascinating article, and of course a surprise as I keep expecting religious Gothic masterpieces. But commerce is its own religion too isn’t it. There is a story told me by some local Brussels friends that the master of works committed suicide when he realised the roof was not symmetrical about the main tower… don’t know if you ever came across that bit of apocryphal legend when you were there…