(7 min read) Antwerp Cathedral — number 40 in my countdown of the Fifty Greatest Works of Gothic — showcases the ambitious architecture of a wealthy late medieval commercial center, and also demonstrates Gothic's resilience through centuries of religious and cultural transformation.

(For more about this series, see the introduction and the countdown.)

Common Name: Antwerp Cathedral

Official Name: Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal (Cathedral of Our Lady)

Location: Antwerp, Belgium

Primary Dates of Gothic Construction: 1352-1521

Why It’s Great

With its rare seven-aisled design and asymmetrical tower, Antwerp Cathedral embodies both the culmination of Brabantine Gothic, as well as Gothic’s ability to adapt and survive through centuries of tumultuous change, from the iconoclastic Beeldenstorm of the Protestant Revolutions to its Counter-Reformation reinvention epitomized by the church’s pair of Rubens masterpieces.

Why It Matters: History and Context

Antwerp Cathedral stands as one of the most compelling examples of the culmination and survival of Gothic architecture, through centuries of both glory and turbulence. Construction began in 1352 when the city first emerged as a major commercial center, with an ambitious seven-aisled plan reflecting the wealth and aspirations of Antwerp's merchant class. Unlike many cathedrals built under royal or aristocratic patronage, Antwerp Cathedral is an example of a religious Gothic structure embodying the pride of a mercantile powerhouse (much like nearby civic masterpiece Brussels Town Hall).

The building's main construction period lasted until 1521, but like many Gothic masterpieces, it was never fully completed according to its original design. Only the north tower (figure 3) reached its intended height of 123 meters, creating the distinctive asymmetrical profile that has defined Antwerp's skyline for centuries.

This architectural quirk unintentionally preserved a visual record of the city's changing fortunes. The southern tower's truncation coincided with economic downturns that redirected resources elsewhere, and this followed soon enough by Protestant Revolution-related damage and problems. In 1566, the cathedral suffered devastating damage during the Beeldenstorm (Iconoclastic Fury), when Calvinist revolutionaries systematically destroyed much of its religious artwork and interior decorations.

This violent episode marked the effective end of the original Gothic movement, as I described in “Two Short Histories of Gothic Architecture,” and it could have relegated Antwerp's cathedral to historical footnote. Instead, the place emerged as something more complex — a Gothic structure that would be renewed multiple times, from the Counter-Reformation’s Baroque period which Peter Paul Rubens here (see below) to some wonderful Revivalist interiors in the 19th and 20th centuries (also see below).

Surviving not only the Beeldenstorm but also the French Revolution, a major fire in 1533, and two World Wars, Antwerp Cathedral stands today as one of the most resilient Gothic structures in Europe — a testament to both the enduring power of Gothic, and the complex religious and cultural transformations that have shaped European history since its heyday.

Photo Tour

Antwerp Cathedral is in the middle of the city’s old town, and hemmed in by other buildings (an uncommon phenomenon, but not unique to this building). So it is difficult to get good photos of it, and impossible to get a feel for the whole building from ground level (figures 6-8).

When you enter the church through the main west entrance you encounter a wide, open, and well-illuminated space (figures 2 & 9-14 show the nave and six side aisles). This is perhaps the best example of how late Brabantine Gothic’s clean detailing, vertical lines, and huge windows can make Gothic look strikingly modern. This is especially the case when the walls were whitewashed, as often happened with post-Reformation churches in eastern Belgium and the Netherlands.

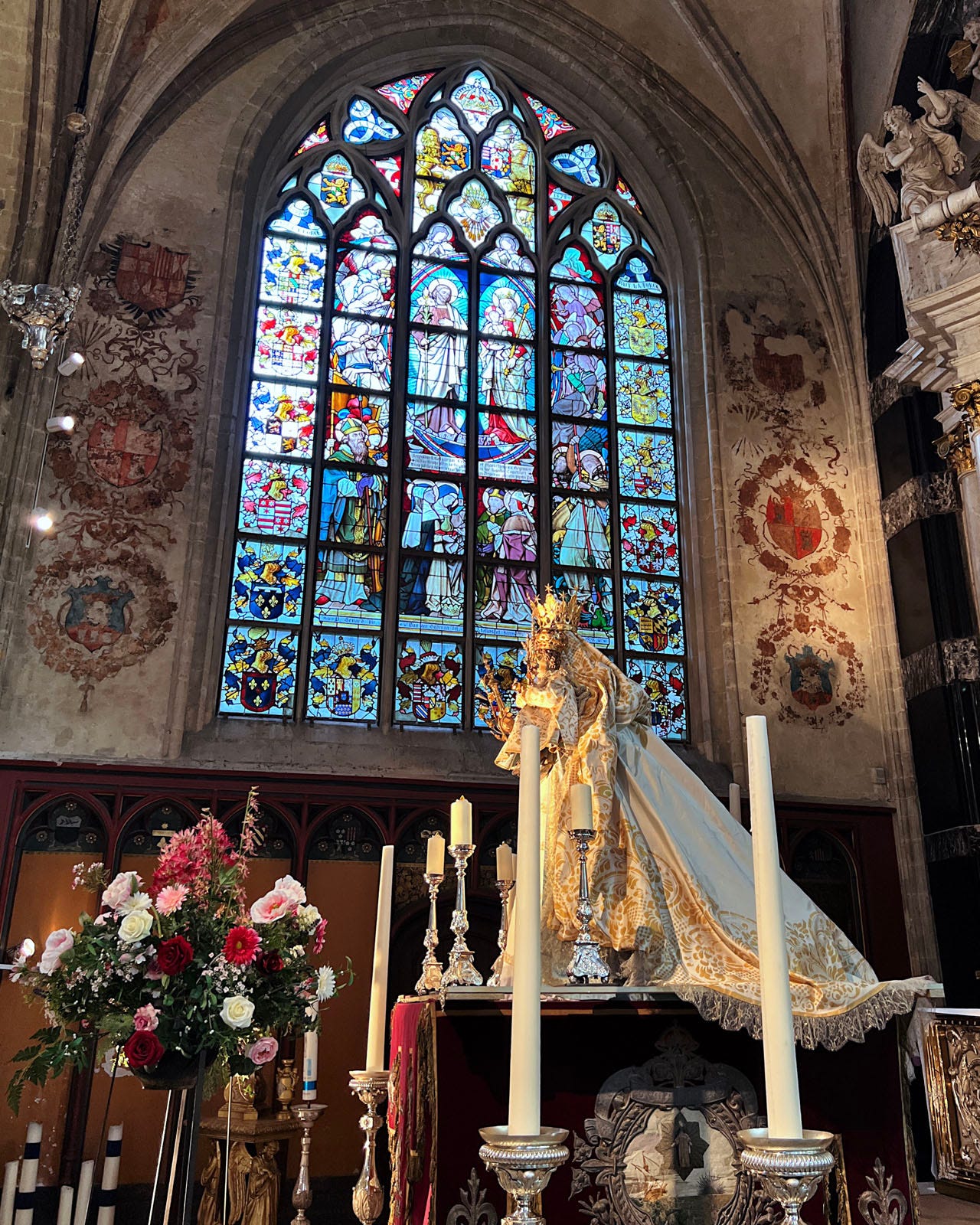

The transepts and crossing (figures 4 & 15-19) are just as light filled as the nave, and in addition to some wonderful 17th century stained glass (figure 17) also have two Rubens masterpieces: a “Raising of the Cross” triptych from 1611 (figure 15) and a “Descent from the Cross” from (see the “In Detail” section below).

The chancel and choir (figures 20-21) have soaring Gothic vaults, and combine with the stunning revival-style choir stalls designed by Frans-Andries Durlet in the 19th century to create a harmonious combination of medieval structure and revival details.

The ambulatory and east side chapels (slides 23-28) were largely redone in an elaborately painted Gothic Revival style, and create a nice counterpoint to the whitewashed western portion of the church.

** Please hit the ❤️ “like” button❤️ if you enjoyed this post; it helps others find it! **

In Detail

For those interested, here’s a detailed look at the masterful Rubens triptych I discussed above:

And a detailed look at a great revivalist interior:

Visiting Advice & Conclusion

My Visit Date: 5 September 2022

Antwerp is a city worth a visit of several days, as I will explain in my next Museum Monday post — don’t just come to the cathedral, there is too much here! The cathedral itself deserves at least 1-2 hours of exploration to fully appreciate its unique seven-aisled layout and the striking contrast between the bright, whitewashed nave and the richly decorated eastern end. If possible, visit on a sunny day, when the light through the enormous windows is particularly spectacular.

Antwerp Cathedral represents a fascinating case study in Gothic architecture's adaptability and resilience. The chuch embodies the story of European culture itself — born in medieval faith, tested by revolution and conflict, and renewed through artistic innovation. While not as purely Gothic as some higher-ranked entries in this countdown, Antwerp Cathedral's unique seven-aisled design and its remarkable survival story make it a very worthy entry in our survey.

Photo 4, looking up in the central crossing tower, is stunning. Even with all the great stained glass pictures in all these structures, sometimes the most breathtaking things are seen by looking straight up.

Glorious photos, Ben!