(8 min read) A special Mother’s Day post, dedicated to my wonderful mom — and to any other mothers out there reading this.

More Popular Than Jesus

In 1966, John Lennon raised a big stink among fundamentalist evangelicals in the US when he said in an interview that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus.” To be fair, he was simply commenting on (in fact, lamenting over) the secular nature of 20th century society, not boasting. But fundamentalists tend not to have much room in their minds for nuance.

And evangelicals tend not to have much room in their religion for the only person in Christianity who truly was “more popular than Jesus,” at least in the High and Late Middle Ages — the Virgin Mary.

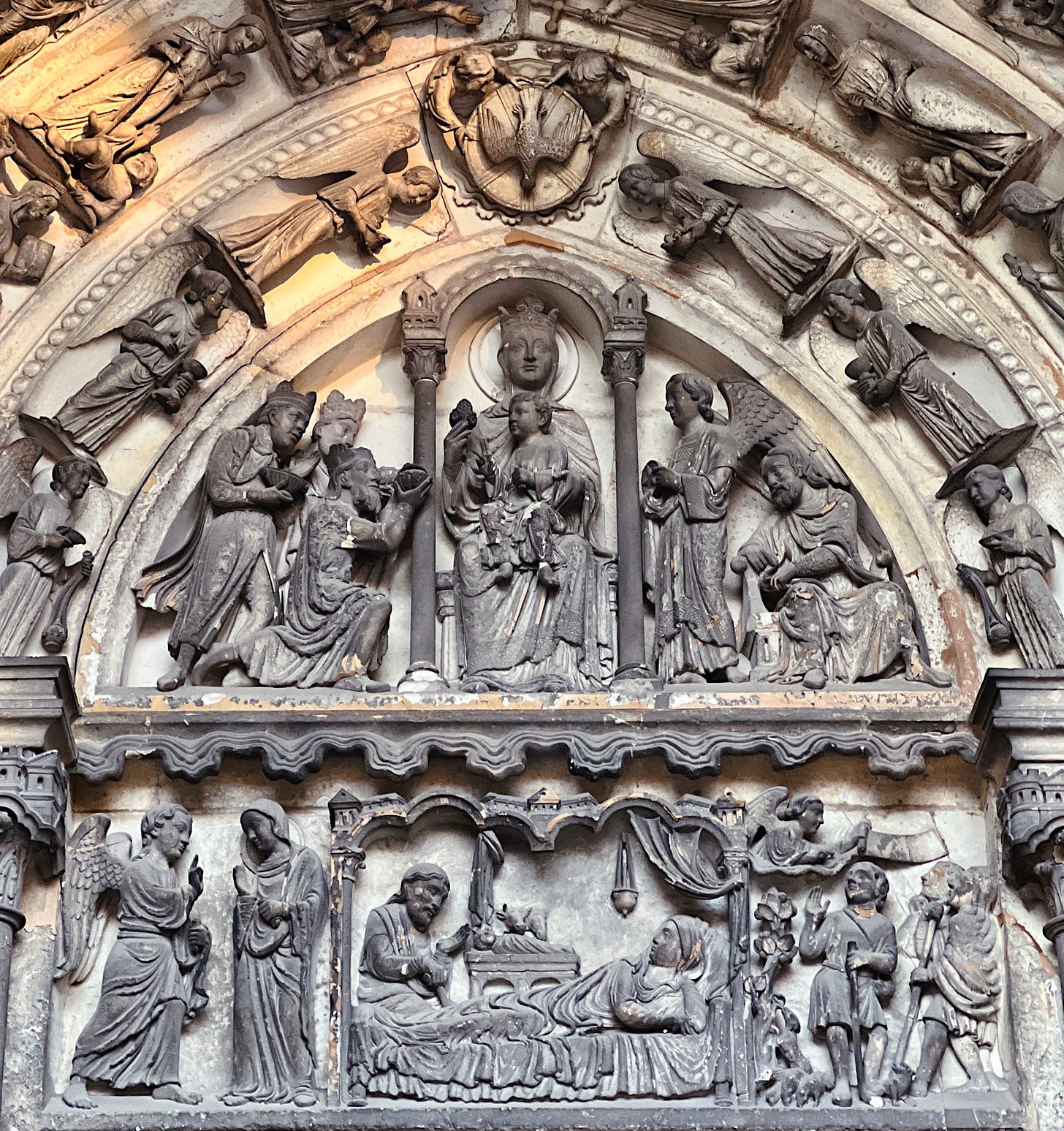

Mary was an important figure in Christianity from the start, of course. But it wasn’t until the 11th and 12th centuries that Marian devotion reached a level on par with the Christ himself, if not perhaps surpassing it.

Not only was every third Gothic cathedral dedicated to “Our Lady” (or so it sometimes seems), but when it comes to the art in Gothic churches, her image strikes me as being more common than Jesus’ (though I’ve never done an actual count).

One of these days — over at The Gothic World — I will do a proper post on Marian veneration in the High and Late Middle Ages. It is a fascinating phenomenon, and almost certainly tied to the contemporaneous flowering of chivalric romance and the ideal of “courtly love.” At that time I’ll also explore the full gamut of her iconography, which is extensive and complex.

This post, however, is not about Mary in general, but rather about how in her most common iconography — holding the Christ child, in many variations and permutations (figures 1-5, 30-31) — she is embodying the positive pole of what Jungians and comparative religionists call the “Great Mother” archetype. (Note that there is a negative pole to this archetype as well, but in this essay we will ignore it.)

(NB: This essay isn’t an argument against Mary’s uniqueness within Christian theology. It’s an invitation to see veneration of her as part of a deeper human pattern — one that predates doctrine, defies dogma, and unites cultures across history.)

The Great Mother

While universal archetypes and universal narratives are out of fashion these days, there can be no denying that — even more so than the “hero’s journey” — the image of the nurturing mother is a truly universal archetype. All individuals have a mother, and any culture that does not revere both the fertility and nurturing aspects of motherhood is destined to die out.

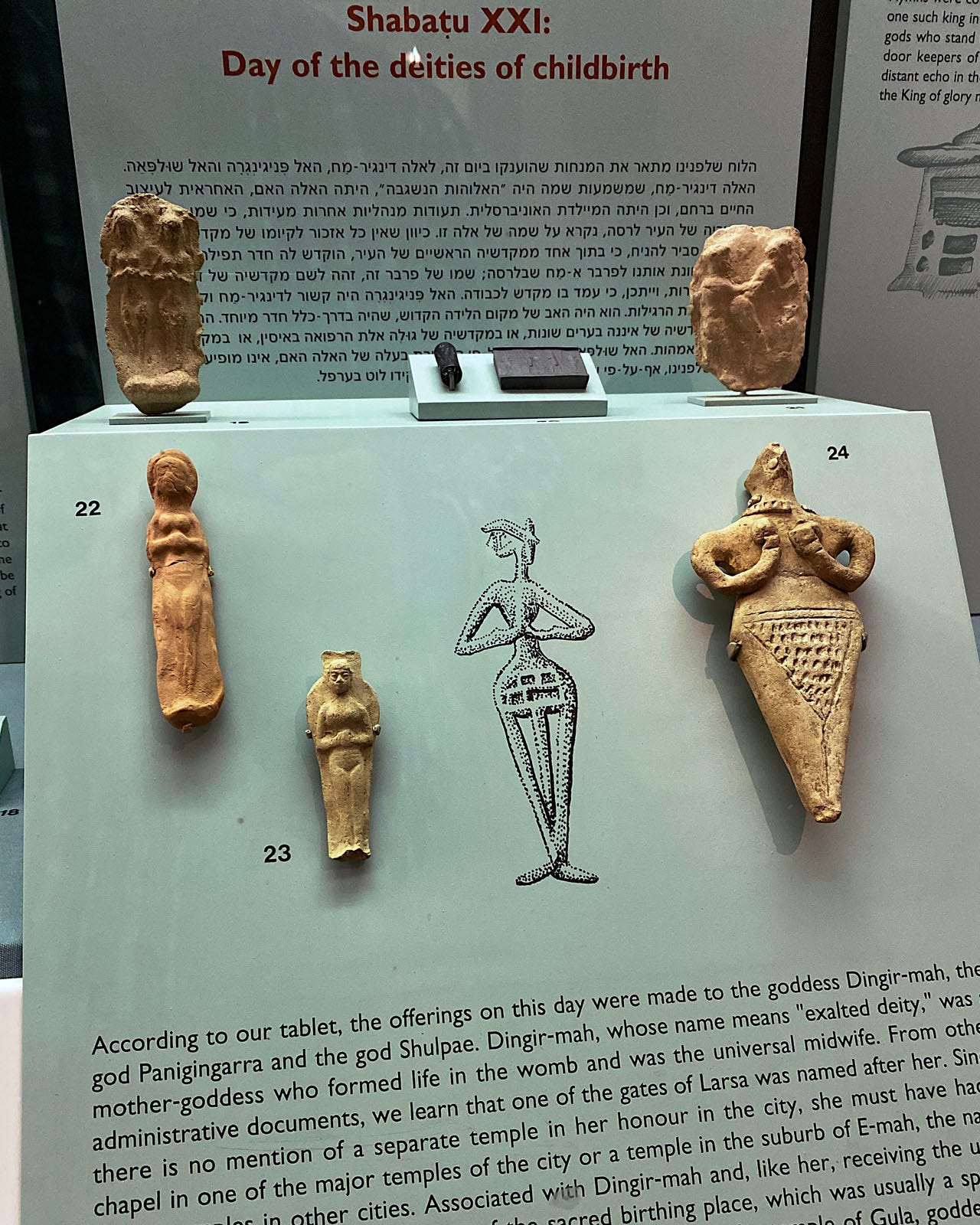

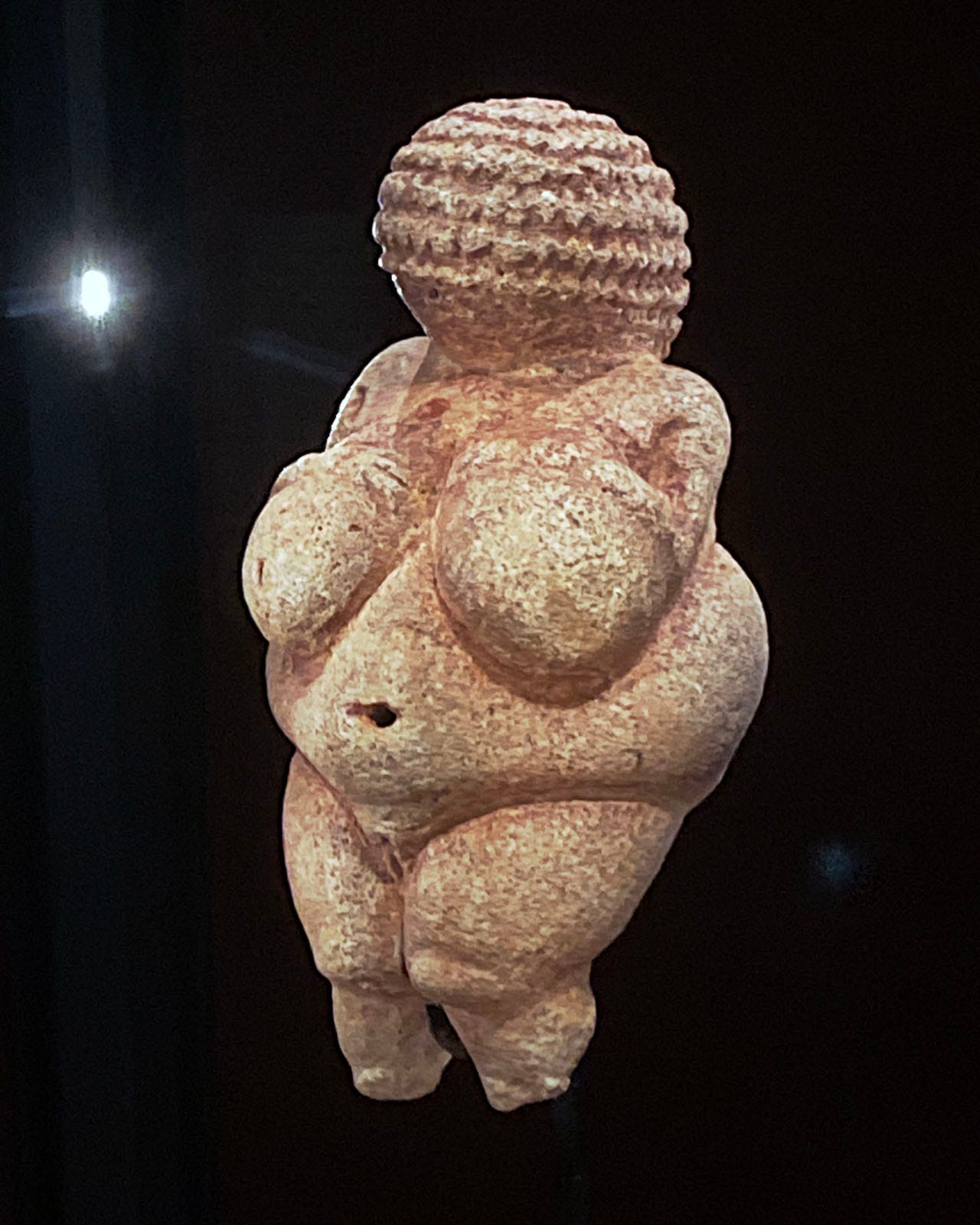

Thus, along with paintings of the hunt (ie, “the hero’s journey”) on cave walls, sculpted fertility figurines are among the earliest representational images humans made — going back nearly 30,000 years (figures 6-8) and radiating life-giving power.

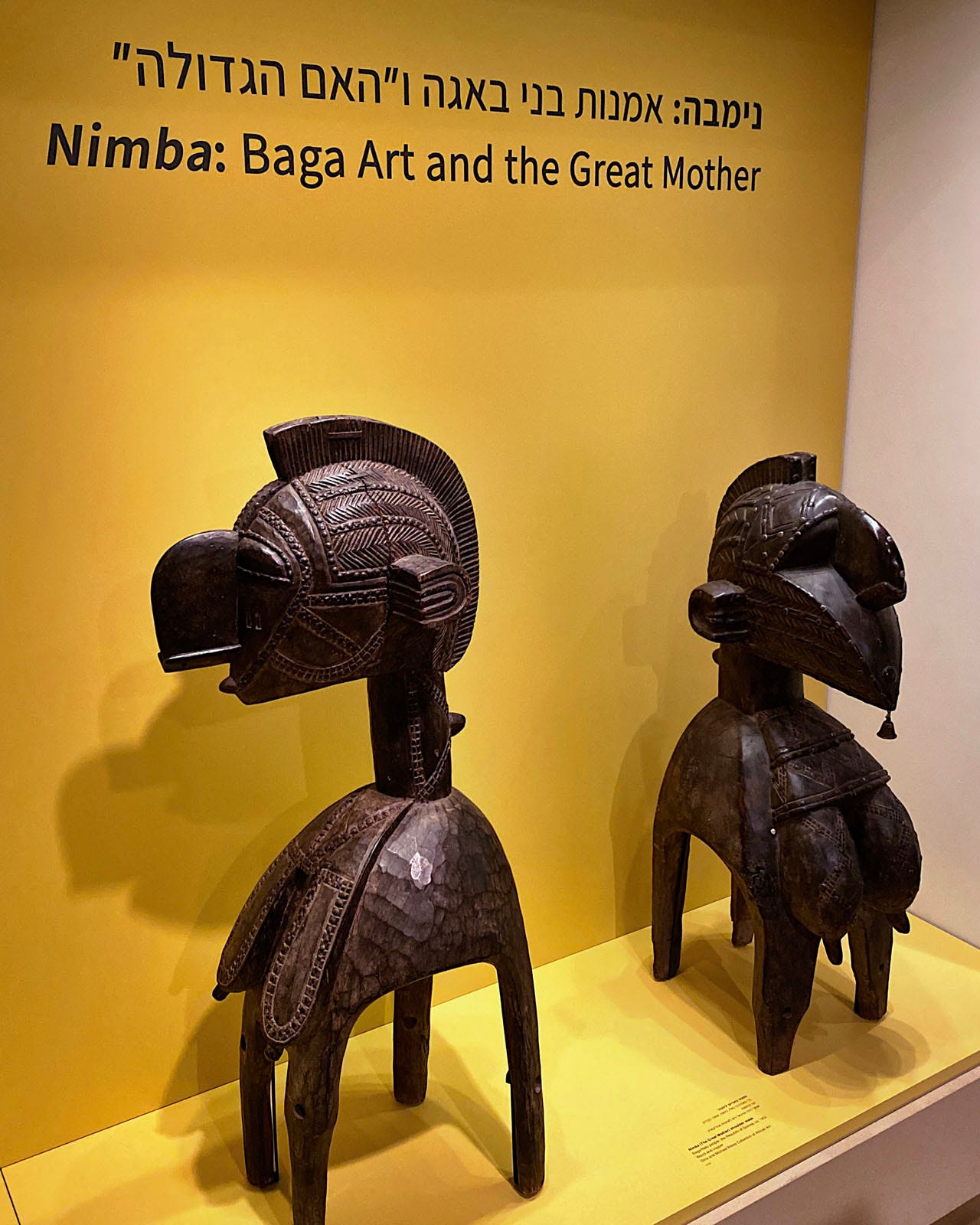

This motif isn’t confined to Paleolithic Europe and Neolithic Anatolia, of course.

The mother goddess appears across every continent, under different names, in different styles — but always in recognizable forms. Figures 9–16 span Iron Age Europe to Pre-Columbian Peru, African tribal traditions to classical Indian religions and Asian Buddhism.

While I cannot say much about the exact names, stories, and rites associated with figures 9-13, figures 14-17 are all of well known figures in the Hindu and Buddhist worlds that come to us with rich traditions.

Guanyin (figure 17) — known as Kannon in Japan— is especially worth singling out as a counterpart to Mary, as we will discuss at the end of this essay. And from my experience visiting temples in Japan and Taiwan, (s)he also seems “more popular” than the Buddha.

The Roots of Marian Iconography

In the Near East — close to the time and place where Christianity emerged — we see even more explicit precursors to the Virgin Mary. Many Mesopotamian goddesses (eg, figure 18) have maternal and fertility associations. But it’s the image of Isis suckling Horus (figures 19–20) that provides the most direct visual lineage.

Isis — an Egyptian goddess whose cult spread across the entire Mediterranean in Hellenistic and Roman times — was often shown seated and suckling the young god Horus (figures 19-20).

(Horus, incidentally, was the son of the sacrificed and reborn god Osiris — sound familiar?)

However, it is in Anatolia where we see the greatest expression of the Mother Goddess in Roman times, and a direct influence on the doctrine of Mary as “Mother of God” (literally Theotokos — “God-Bearer”).

Kybele seems to have originated in Phrygia (central Anatolia) in the early first millennium BC, though the mother goddess of Catalhoyuk (figure 7) suggests that similar ideas go much further back in the region.

By Hellenistic and Roman times, Kybele was known as “Mother of the Gods” and her worship was as widespread as Isis’, though centered in Anatolia, not Egypt. By Hellenistic times she was also most widely portrayed as enthroned and with a lion in her lap or two at her sides, though many variations on this theme exist (figures 21-26).

In addition, as with most gods and goddesses of the ancient world, identities and iconography were fluid.

Figure 27, for example, shows both Aphrodite and Kybele in costumes more typically associated with Artemis of Ephesus (figure 28). All of these goddesses had fertility and nurturing aspects, and should be seen as expressions of the Great Mother archetype.

The connection with Artemis of Ephesus — whose temple was one of the seven wonders of the ancient world — is important, because it was here that theChurch Fathers explicitly decided that Mary’s role in the Christian church would be that of the Great Mother.

The Council of Ephesus

It can be no coincidence that the Third Ecumenical Council — convened to determine doctrinal finality on the role of Mary within Christianity — was held just a mile from Artemis’ temple, as this was the most important center of Great Mother worship in the Mediterranean.

Christianity’s spread required the assimilation of local beliefs into the wider pantheon of saints and stories that make medieval Christianity so rich. Just as the Celtic goddess Brigid became St Brigid of Kildare, and St George absorbed the story of Perseus, Mary — mother of the Christ — was deemed at the Council of Ephesus in 431 to absorb and refract the role of Kybele, Meter Theon (“Mother of the Gods”).

There is perhaps a deeper wisdom in this conciliar decision. Any religious tradition that cannot accommodate the feminine aspect of creation and divinity is inevitably lop-sided and destined to become problematic. By elevating Mary to Theotokos (“God-Bearer”), Christianity found its Great Mother — not as a separate goddess, but as an essential part of the divine story, balancing the otherwise overwhelmingly masculine imagery that dominates Christian theology.

In iconography, this is most obviously seen in Mary as the “Throne of Wisdom” (figures 3 & 30), but it pervades other related imagery regarding her as well.

By the late Middle Ages, the role of Great Mother was also absorbed by St Anne, Mary’s mother, as you can see in figure 32.

And as ecumenical thinking has spread in more modern times, those with artistic vision have been able to see Mary in all child-bearing women, recognizing the universal in the particular (figure 33).

Maria Kannon

To brings things full circle, a little known fact about Edo-era Japan also tells us how — in addition to Christianity absorbing other traditions — non-Christian deities could also absorb Marian worship, if and when necessary.

Christianity was outlawed in Japan in 1614, and all missionaries expelled. However, during the sixty years of missionary work preceding that edict, many Japanese had become Christians, and continued to practice the religion in secrecy.

These crypto-Christians were able to venerate images of Mary by repurposing images of Kannon with a child (figures 17 & 34). Authorities couldn’t tell the difference between them.

Can you?

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

Thank you for the dedication. I enjoyed it and learned from it.