(8 min read) This is an introductory and summary post for an extended series which uses a big-picture, historical lens to examine the current state of disorder in geopolitics and grapple with the forces causing it.

Preface

[EDIT: This series has been published on Amazon as a short kindle book; it is currently available on kindle unlimited and Parts I-V cannot therefore be published elsewhere. Read it for free on kindle unlimited, or buy the kindle version for $1.99.

This introductory essay is still available, however, and provides an outline to the book’s overall arc and argument.]

This series — which is essentially a single extended essay — brings together ideas that I’ve been mulling over and doing “side research” on for several years, though I didn’t begin writing until earlier this month.

As one might expect for something that’s been percolating in the back of my mind for so long, it soon became very clear that the essay would also be very long. Since I aim to keep my posts here to a maximum of ten minutes reading time, I have decided to break up the piece into five posts (plus this introduction), which will appear every Wednesday through March 5th.

This post is meant to serve as a reference point for the entire series. A section for each of the five main essays is below — this includes an image, title, and short summary of the main arguments and key ideas I’ll explore. If you decide not to read the entire series, these summaries will give you a sense of the overarching argument and allow you to decide which posts are of most interest to you. I’ll also update this page with links to each essay as they go live, so it can act as a central hub for the series.

I am not footnoting these essays. I am, however, including a short form “Suggested Reading & Bibliography” at the end of this introduction which includes the most relevant books I’ve drawn on and which may give you an idea of where I am coming from. In addition, when I express ideas that I think are either contestable or not mainstream knowledge, I will parenthetically reference the authors whose work informed my statement.

Introduction

Geopolitics is in a state of serious disorder. The narrative driving the last thirty — if not eighty — years of geopolitical discussion was one where increasing globalization and democratic liberalism (in its broader sense) promised a world of increased wealth, an expansion of human rights, and an interconnected global communit with shared norms. But over the last decade that narrative has been roundly rejected by broad swaths of the globe, including by significant populations in the nations from which it originated.

This rejection is part of a more general trend: the unraveling of institutional authority across nearly every domain of society, from politics and economics to education and culture.

As a part of this broader trend, existing relationships both within and between nations are breaking down, along with the rules and norms that have governed those relations since the end of World War II. For the first time in generations, it is essentially impossible to predict what the next decade holds for the world.

To make sense of such upheaval, I believe it is necessary to take a big step back — not just a few decades, but many centuries, if not millennia. My approach here is basically this — by looking at historical precedents and analyzing how shifts in communication and shared narratives have shaped collective identities and political orders, we may gain some perspective on what is happening now.

This series will examine the topic through some “big-picture” lenses and historical case studies. The first post will lay out those lenses, examining the role of communications media and shared narratives in the creation and maintenance of bodies politic. The second and third posts will explore historical case studies where media revolutions reshaped social orders. The final two posts will turn to the present and future, using the insights gained from the first three.

Part I: The Nature of Bodies Politic & The Role of Media

(Full post here.) This post describes the nature of collective entities, from small groups like sports teams to broad cultural structures like societies and nations. I focus particularly on bodies politic and the shared narratives, myths, and symbols that hold them together. These shared narratives form a central element of individuals’ identities and likewise define the group’s identity. Without them, collective entities cannot exist.

I also discuss in this post how the dominant forms of communication in a given society shape the both the kinds of narratives that can be told and the structures of the societies they hold together. Historically, as new forms of communications media have appeared, they have disrupted existing social orders, sometimes violently, before societies adapted. Understanding this dynamic is key to making sense of the disorder we see today.

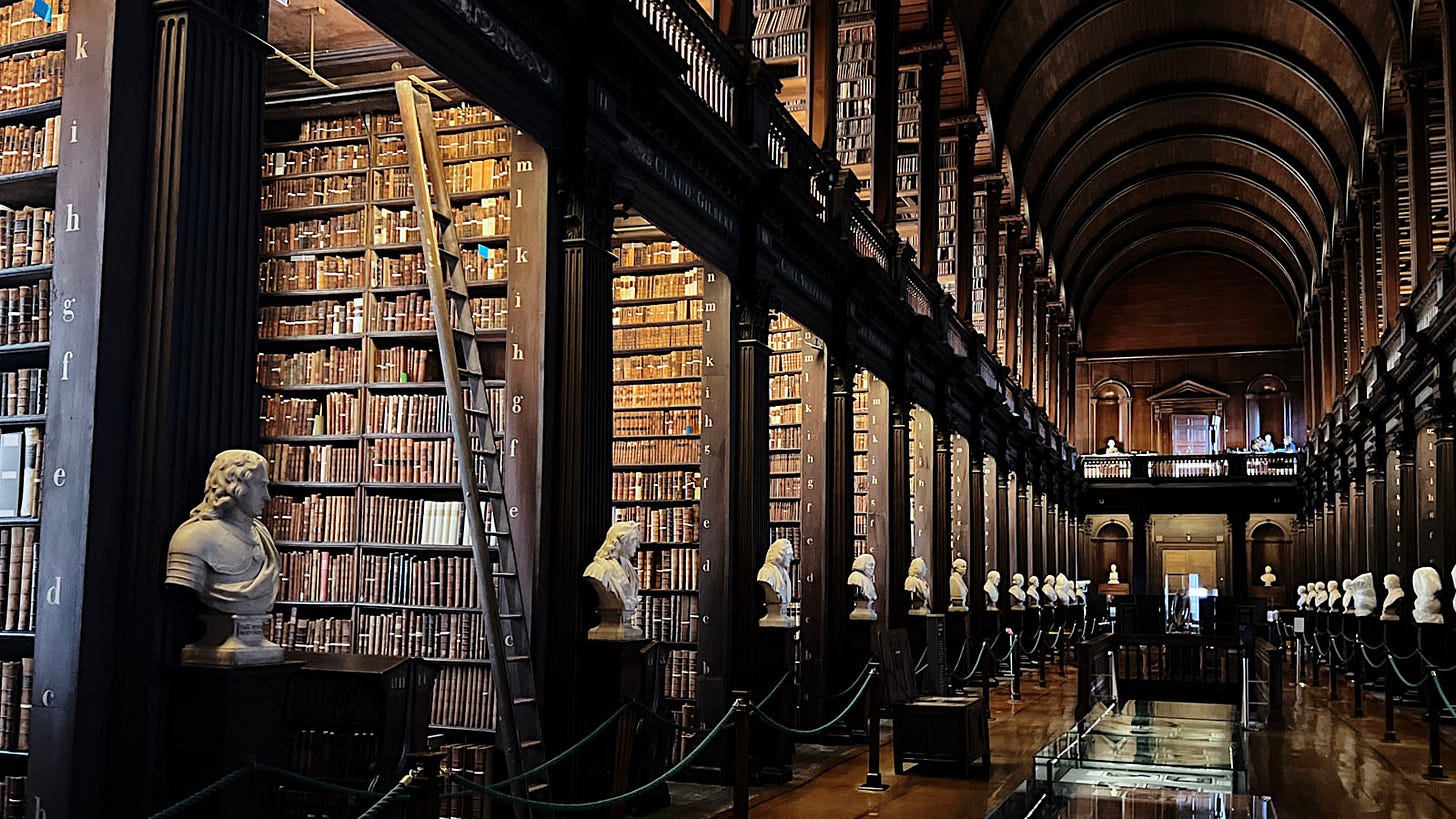

Part II: The Printing Press & The Protestant Revolutions

(Full post here.) The second essay examines how the printing press supercharged the so-called Protestant Reformation of 16th centry Europe, which would be better called the “Protestant Revolutions.” The issues being fought over were not purely “religious” in the modern sense of the term, but deeply political and economic as well. They also unfolded differently across different parts of Europe, and were almost always accompanied by radicalism and violence.

The spread of the printing press, which started in the second half of the 15th century, altered the dynamics of power by greatly democratizing access to written communication. This undermined the medieval social order, which had been held together by a tightly controlled narrative disseminated through manuscripts and oral tradition. The result was the collapse of Christendom as a unifying body politic, leaving Europe more fragmented and chaotic for for centuries.

Part III: The Birth of Nation-States & Today’s World Order

(Full post here.) This third post is about the centuries-long creation of today’s geopolitical order, which is based on the primacy of nation-states as bodies politic and a set of rules and norms around which they relate to each other.

The modern nation-state is a child of the Enlightenment, with the births of the United States and France leading the way for others. Over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, mass media played a crucial role in forging the shared narratives that bound people together as nations. These narratives were often consciously constructed, drawing on both reinterpretations of historical traditions and newly invented symbols.

By the end of World War II, and as solidified by the founding of the United Nations, the nation-state had become the de facto framework for political order.

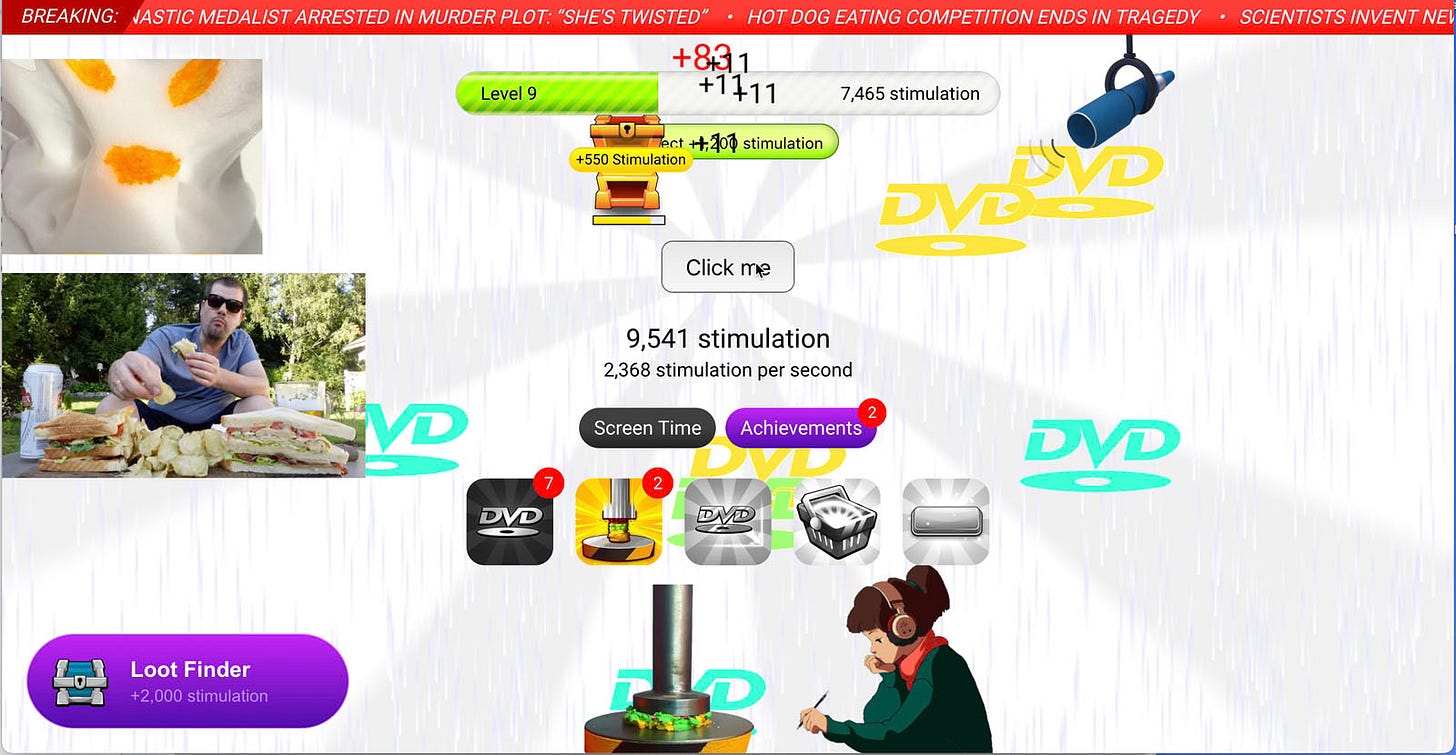

Part IV: The Internet & Today’s Dis-Order

(Full post here.) The fourth essay brings the discussion to the present. Building on the analyses in the earlier essays, I argue that the internet is disrupting the existing global order much as the printing press disrupted medieval Christendom. The internet has radically democratized access to information and communication, undermining the centralized control over shared narratives that mass media provided to large institutions in the 20th century.

As in 16th century Europe, today’s internet-driven upheavals are transforming what were once calls for patient reform into radical demands for destruction and revolution. The shared narratives that have held bodies politic together are fragmenting, leading to polarization, distrust, and the collapse of institutional authority.

Part V: New Media & New Orders

(Full post here.) By the end of the fourth post, you might agree with me that the era of the nation-state’s primacy may well be ending, even if nation-states themselves continue to exist as historical artifacts. If so, what might take their place?

In this (very) speculative (and necessarily inconclusive) conclusion to the series, I explore possible futures for collective identity and global governance. I also lay out the basics of the newest form of media currently emerging and suggest some wasy to think about future events as they unfold.

** Please hit the ❤️ “like” button❤️ if you enjoyed this post; it helps others find it! **

Suggested Reading & Bibliography

The below is divided in two parts. First are the books specifically related to collective entities and media studies; these generally fall into genres such as anthropology, sociology, philosophy, cultural criticism, and specific histories. These books are the most obviously relevant to the ideas and arguments in this series.

However, I have also read many dozens of “general histories” of the regions and eras I discuss. While not central to my arguments, these form my background historical understanding, and so I have decided to include a curated selection these general histories as well, below the first list.

Collective Entities & Media Studies

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. 1983.

Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Roots of the American Revolution. 1967.

Berger, Peter & Thomas Luckmann. The Social Construction of Reality. 1966.

Carr, Nicholas. The Shallows. 2010.

Clarke, Andy. The Experience Machine. 2023.

Durkheim, Emile. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. 1912.

Eliade, Mircea. The Sacred and the Profane. 1957.

Eisenstein, Elizabeth. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. 1979.

Fukuyama, Francis. The Origins of Political Order. 2011.

Fukuyama, Francis. Political Order and Political Decay. 2014.

Fustel de Coulanges, Numa. The Ancient City. 1864.

Grosby, Steven. Nationalism. 2005.

Gurri, Martin. The Revolt of the Public. 2018.

Harari, Yuval Noah. Sapiens. 2015.

Harari, Yuval Noah. Nexus. 2024.

Henrich, Joseph. The Secret of Our Success. 2015.

Innis, Harold. Empire and Communications. 1950.

Man, John. The Gutenberg Revolution. 2002.

Massing, Michael. Fatal Discord. 2018.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media. 1964.

Ong, Walter. Orality and Literacy. 1982.

Pettegree, Andrew. The Book in the Renaissance. 2010.

Pettegree, Andrew. The Invention of News. 2014.

Poe, Marshall. A History of Communications. 2011.

Postman, Neil. Amusing Ourselves to Death. 1985.

Searle, John. The Construction of Social Reality. 1995.

Taylor, Charles. Sources of the Self. 1989.

Woodard, Colin. American Nations. 2011.

Relevant General Histories

Blanning, Tim. The Pursuit of Glory. 2008.

Evans, Richard. The Pursuit of Power. 2017.

Greengrass, Mark. Christendom Destroyed. 2014.

Holcombe, Charles. A History of East Asia. 2017.

Jordan, William. Europe in the High Middle Ages. 2004.

Keay, John. India. 2010.

Kriwaczek, Paul. Babylon. 2010.

MacCulloch, Diarmond. The Reformation. 2013.

Madigan, Kevin. Medieval Christianity. 2015.

Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause. 1982.

Price, Simon & Peter Thonemann. The Birth of Classical Europe. 2011.

Rady, Martyn. The Middle Kingdoms. 2023.

Scribner, RW. The German Reformation. 1988.

Wilkinson, Toby. The Rise and Fall of Ancient Egypt. 2010.

Williamson, Edwin. The Penguin History of Latin America. 2009.