(5 min read) 9,000-year-old Catalhoyuk was humanity's first urban experiment — a densely packed settlement where people entered houses through rooftops and buried their dead under the floors.

Overview

When I was around ten, I remember hearing about Catal Huyuk — whether it was through school, National Geographic, or a library book, I can't recall. But the place stuck in my memory: 9,000 years old, humanity's first “city,” with densely packed houses in a honeycomb layout and entrances through the roofs. It captured my boyish imagination and that’s how I remembered it for decades.

This was the 1980s, and archaeological findings evolve. It’s now known as Çatalhöyük in proper Turkish, and no longer considered the first settlement — that honor goes to the Natufians, whose settlements in the Levant precede Catalhoyuk by a couple millennia.

If there's one lesson from recent archaeological research, it’s that prehistoric “firsts” — fire, domestication, tools, art, language, agriculture — keep getting pushed back in time. And settlements are no exception.

That said, the Natufians’ settlements were never as large or densely packed as Catalhoyuk, so I think it is fair to say that Catalhoyuk is still — for the time being and as far as we know — humanity’s earliest urban environment.

With that accolade in mind and my boyish imagination still fired, I decided to take a short detour on my drive through Tukey in 2022 and visit the site, located in the Konya Plain.

Catalhoyuk was occupied from roughly 7100 to 5600 BCE, with perhaps as many as 8,000 inhabitants at its peak. British archaeologist James Mellaart began excavations in the late 1950s, revealing this remarkable experiment in urban density.

The site itself — mostly stone foundations and low walls — isn’t much to look at (figures 2-3), but on-site reconstructions of four homes made in 2017 (figures 4-11) help visitors understand how these spaces functioned. And Ankara's Museum of Anatolian Civilizations has a wealth of artifacts from here (figures 12-13 & “Art in Detail”).

What made Catalhoyuk revolutionary was how people lived. Houses shared walls in a honeycomb pattern with no streets — residents moved across rooftops and entered homes through openings in the roof.

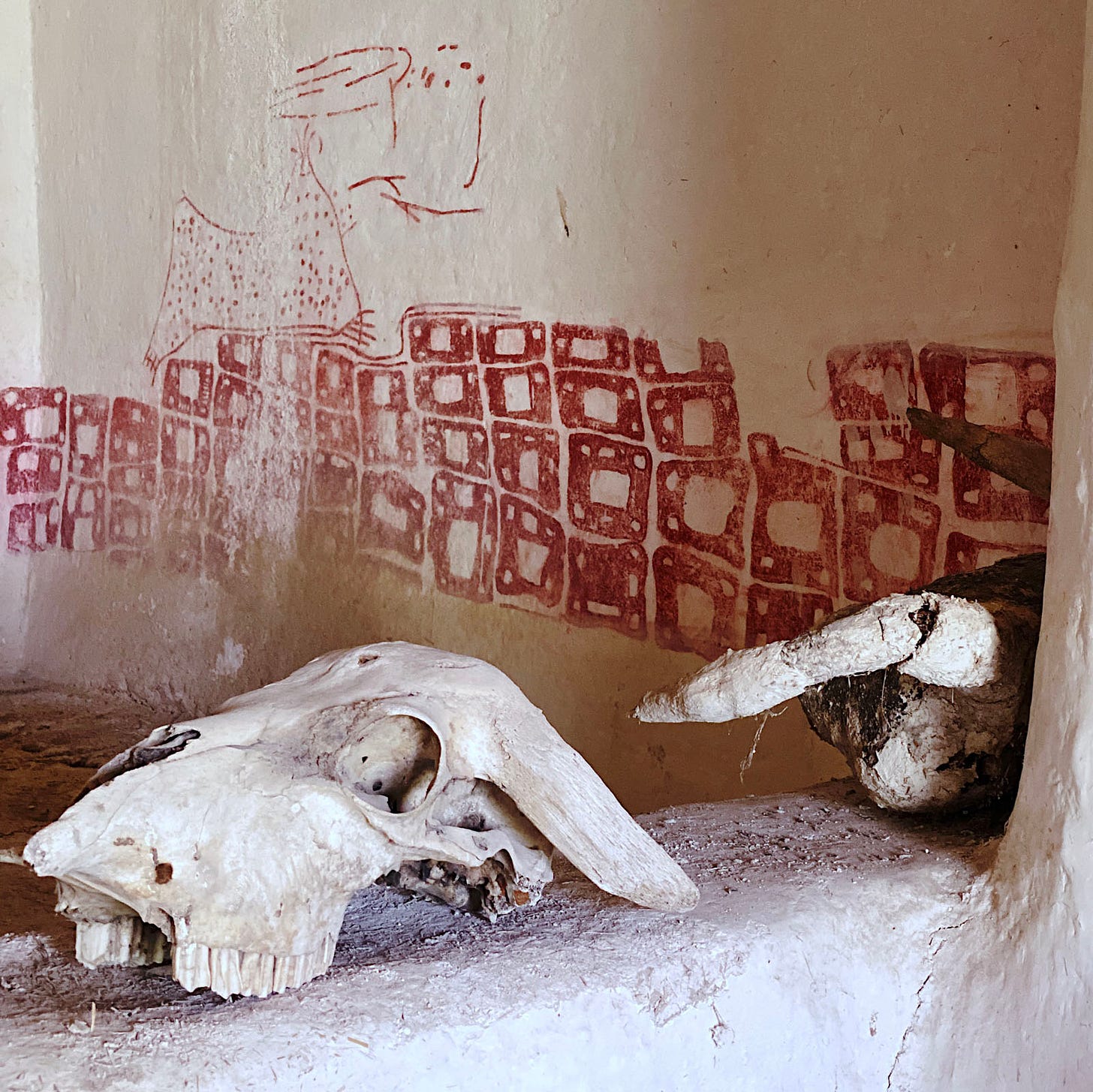

Inside, living was surprisingly sophisticated (for the time). Raised platforms served as sleeping areas and work spaces. Wall paintings depicted hunting scenes, geometric patterns, and religious imagery.

Most remarkably, the dead were buried directly under the house floors, creating an intimate relationship between the living and their ancestors that would influence religious practice for millennia. In addition, animal skulls — particularly aurochs (wild cattle) — were embedded in the structures as ritual objects.

The people of Catalhoyuk lived without obvious social hierarchy — houses were remarkably similar in size and layout, suggesting an egalitarian society. They were skilled craftspeople, working obsidian from distant volcanoes into razor-sharp tools and mirrors, creating elaborate textiles, and fashioning clay figurines. Their economy mixed early agriculture with hunting and gathering: they grew wheat and barley while still hunting wild cattle, deer, and boar.

Their religious life centered on fertility, animals, and the cycles of death and rebirth. The famous “Goddess Figurine” (figure 13) — a seated female figure flanked by leopards — suggests sophisticated concepts of divine femininity that would echo through Anatolian religion for millennia. (I discuss this figure and Anatolian mother goddesses more fully in The Great Mother).

At Catalhoyuk, we glimpse not just humanity’s first urban experiment, but the deep roots of religious traditions that would shape the ancient world.

** Please like and/or restack this post if you enjoyed it; it helps others to find it! **

Art in Detail

This embedded Substack Note shows artifacts from Catalhoyuk that are now located in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations — including figurines, tools, weapons and pottery:

Practical Information

Where: 24 miles (40km) SE of Konya, Turkey.

My Visit: 29 May 2022

Best For: Enthusiasts of prehistoric archeology and early human culture.

Pro Tips: The informational plaques were sparse when I visited, and it is best to know a fair amount in advance about the place (and prehistoric Anatolia in general) before visiting. That said, a new visitor center opened on the site in late 2023 — well after I visited — which looks to have a lot of good multimedia kiosks and informational plaques.

Konya is a large city and a fine place to spend the night; it also has an archeological museum worth a visit. (And if you are coming this far, you simply must visit the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, the wonderland of Cappadocia, and the tons of other prehistoric and ancient sites all around… (if you can’t tell, I am a big fan of Turkey! : )))

Really enjoy these formative influence posts...

I enjoyed this! Thank you! I learned about Catal Huyuk in college and am glad to have had you bring me up to date and add to my knowledge.